Why didn't Sauron own a Lockheed AC-130 gunship?

Why Hasn't Middle-Earth had an Industrial Revolution? Part III

I. Introduction

Much like Gandalf the White, this series has been resurrected from seeming death many months later, the explanation for which shall only be fully released in a grab-bag collection of my works published many years after my death to middling reception.12

For those joining us for the first time, this series is (nominally) a review of the realism of the economic forces in J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle Earth. Specifically, it focuses on the question of why Middle Earth does not seem to be experiencing the sustained economic growth we do in the real world.

Yes, this is a dumb question.

Yes, the quality of the books is largely orthogonal to whether or not Mordor’s GNP goes up and right on charts.

No, I will not finish the books before writing this, stop yelling “finish the books” at my house, I will never finish the books, coward.

When we last left off, I had spent, uh…. ~12,000 words arguing that Middle Earth had the right natural resources to industrialize and that even though it didn’t have a culture of scientific discovery, it probably should have.

Of course, just because the right raw materials were there and people (should have) had the right mindset to invent stuff, doesn’t mean you are just going to get to industrialization. People, as a general rule, aren’t just milling around in a perfectly harmonious anarchist commune doing whatever they want.3 There are rules and structures that govern how we interact with each other and who gets to say things like “Give me all your money or my soldiers will shoot you”.

As it happens, the person who gets to say things like “give me all your money or my soldiers will shoot you” is usually in charge of the government and calls this taxation. People generally think how this works is important for economic growth.

This specific post, as promised, focuses on the interaction between these sorts of “Institutions” and economic growth, institutions being something like political constraints and/or ‘the rules of the game’ that structure how we interact with one another. It is also, somehow, roughly 1/4th the length of a small book. I wish this were not the case, both for my sanity and also because it would have been done much quicker, but alas here we are.

I.A. Tolkien and Institutions

As has been noted by lots and lots and lots of people in past comments, Tolkien wasn’t particularly interested in economics and it goes largely ignored (excepting the themes of anti-industrialism in LOTR) throughout his books. This is entirely reasonable for the purposes of writing a children’s series, indeed, it would be weird if Frodo and Gandalf paused in the middle of their journey to Mordor to discuss exactly which type of account at the National Bank of Gondor offered the highest rate of risk adjusted returns.4 5

However, I think we can reconstruct at least an approximation of how Tolkien models the relationship between institutions and economic growth.

Put simply, I don’t think the world of Lord of the Rings behaves as if institutions have a meaningful effect on economic growth. We get depictions of a largely static (or slowly declining) world that seems to behave roughly similar regardless of the overall structure of society. This is sensible given the ‘pastoral’ values that are often attributed to Tolkien, where independent local farms that are largely removed from market transactions are envisaged as a desirable endpoint for humanity.6

If we wanted to put this slightly more formally:

Let X be any given index of ‘institutions’ and let Y be GDP per capita.

For all possible X, X ⫫ Y

Alternatively:

The equation for GDP/capita in Middle Earth can be given by:

Y = aZ + bX

Where a and b are constants and Z is a vector of everything that determines GDP that is not institutions.

In Tolkien’s view: b = 0

There are, of course, a few counterexamples to this claim being an accurate model of Tolkien’s thought. Trivially, the political institutions that resulted in Numenor invading the undying lands caused GDP to go to zero, because everyone was dead.7 8 Similarly, if Sauron succeeded in conquering Middle-Earth, I think that would hurt the economy? To be perfectly honest, I’ve never exactly understood what Sauron actually wants to do if he wins, but the vibes are off, so I’m going to assume he would do negative things that would make it harder to grow the economy.

Finally, as we’ve touched on before, in a lot of peoples view this isn’t entirely true because both Isengard and Mordor may have had top down ordered industrialization that affected the economy. My view on this is that this was less industrialization and more burning lots of trees to make swords, which is a thing people have done forever, but pollution is definitely a negative externality and so GDP varies at least somewhat with the institution of dictatorship.

So, we might want to reformulate our statement to be a slightly weaker version:

Let X be any given index of ‘institutions’ and let Y be GDP per capita.

For all most all possible X, X ⫫ Y

Thus, we have two questions we can think about here. First, is Tolkien’s (implicit) model of how institutions relate to growth correct? I think no.

Second, are the institutions of Middle Earth arranged in a way that we would expect sustained growth/an Industrial Revolution? I think (maybe) no here as well (but that it’s sort of weird that this is the case).

What follows is my attempt to argue for both of these claims.

I.B. What, like, even is an Institution, man?

So, back to institutions. This is a very popular explanation for economic growth, largely, I think, because of the absurd success of Acemoglu and Robinson’s Why Nations Fail, which credits institutions with being the main explanation for divergence in economic outcomes around the world.9 10 Also, I think, because there is a certain appeal to “Institutions” being the reason a country can or can’t grow.

Institutions are mutable. You can (theoretically) swap out the bad ones for good ones. It’s very nice to think that if only we could fiddle with some laws everyone might ‘get to Denmark’.11 That is, if institutions are the main cause of growth, there are concrete takeaways about how to grow your economy that aren’t available if you think something like, say, geography is the fundamental driver of growth.12 At least, unless there are some people proposing massive airlifts of water and refrigerants to the Sahara that I’ve missed.

I, like most people I think, would like the institutional thesis to be true, because it suggests potential changeability and also because it just sort of aligns with my interests and view of the world.

My main problem with it, unfortunately, is that when you stop to think about, like, what an “institution” even is, you begin to stare down an unending dark void of eldritch horrors filled with meaninglessness and terminological confusion.

North (1990) is the classical reference people have for institutions and economics and it refers to institutions as “the rules of the game” or, putting it a bit more elaborately: “the humanly devised constraints that structure human interactions. They are made up of formal constraints (rules, laws, constitutions), informal constraints (norms of behavior, convention, and self-imposed codes of conduct), and their enforcement characteristics.”

To be fair, that’s a pretty comprehensive definition, but, and this is a big but, it also doesn’t really make sense.

Like, if you and I are having a conversation and, out of nowhere, I tell you that “if you mention the Eiffel Tower, I will punch you in the face” that technically is a humanly devised constraint!

But, it’s also obviously not an institution.

That is sort of a silly example, but I think it gets at a real problem with a lot of institutional theories; most are not really about institutions but about power.

The reasoning here is that a lot of theories act like institutions have some sort of ability to compel people to behave according to their constraints e.g. the only way to amend a constitution is with a 2/3rds vote in parliament or whatever. But like, this is obviously not true?

The reason you can’t just amend the constitution to make yourself queen for the year isn’t because the constitution says so per se, but because no one will take you seriously or, if they do, everyone will gang up and kick the shit out of you for trying to become a monarch. That is, the institution of the constitution itself has no way to stop you.13

Similarly my declaration that I will punch you in the face isn’t what is stopping you bringing up the Eiffel Tower. What’s stopping you from bringing it up is the fear that I will actually punch you in the face.

So, the definition of institutions as constraints on how we behave doesn’t really make sense. Also, the “constraints” framing leaves out a lot of things we typically imagine are a part of institutions. If the Bureau of Making Sure Orphans Don’t Starve To Death misplaces a bunch of paperwork and forgets to feed some orphans, nothing has changed in the rules of the game, the Bureau is probably still legally required to feed starving children, but nonetheless children have starved and we think that is in some meaningful sense an institutional failure.

A better way of conceptualizing institutions, I hope, is to think of the word ‘institutions’ as referring to a fairly wide set of things where exactly what makes each thing an institution can vary.

Of course, this isn’t very helpful for thinking about how institutions can cause growth, but, for our purposes, I think applying the “Looks like an institution. Quacks like an institution. Probably an institution” test where you sort of can just tell will do fine, leaving the precise word games about what counts to philosophy.

II. The Extraction Thesis

Let’s aside the naval-gazing about what institutions are for now. One model for how institutions effect growth is that “bad” institutions 1. Inhibit Growth and 2. Preserve Themself, so that countries with suboptimal governance are stuck in a bad equilibrium. This is the “Extractive Institutions” thesis of Why Nations Fail and probably the most popular story about institution and long run growth.14

Let’s start by thinking about 1, because I think it is nonobvious why, say, a dictator should be less concerned about the economy than a democratically elected congress.15

The first reason is that dictators don’t internalize the cost of taxation. We would expect a dictator to be interested in the sort of stereotypical lavish consumption associated with, you know, dictators, and therefore to set taxes really high to maximize their personal income. This is probably higher than the tax rate that would maximize the overall wellbeing, given that that money they are taking isn’t being used to do anything useful.

Put simply, If I am a prospective inventor with the right raw materials who is considering investing a lot of money into making a new machine, it’s probably worth considering the probability that the king is going to come along and say “Hm yes this is such a great new machine you have invented, it is going to make me a lot of money”. Of course you might try to say something like“Sorry, I think you meant that I am going to make a lot of money and then pay a reasonable percentage of that profit in taxation” at which point the king will turn to his heavily armed soldiers and say “No I am pretty sure I meant that it will make me a lot of money” and then he will take your machine and probably throw you in prison.

This is not very optimal for invention and economic growth, but it is very optimal for the king, who is going to be very wealthy from expropriating the hard work of people who generate economic activity.16

Under a democratic government, the people involved in setting the tax rate are, at least somewhat, also the people who are affected by the taxes. Given this internalization of costs, we should expect democracies to have lower tax burdens (at least in cases where taxes are just frivolously whiled away on non-productive uses).17

I think a valid complaint about this theory is that it isn’t fair to portray dictators as uninterested in growth. Sure, if taxes were a one time thing, that might be true, but most people pay them more than once. Shouldn’t a dictator try to avoid overly burdensome stealing from his subjects and instead maximize growth so they can get more taxation in the future? Theoretically yes, but dictatorship isn’t exactly known for being a stable occupation.

This uncertainty and risk of assassination, overthrow, etc means that dictators also have relatively short time horizons compared to more democratic governments. If I think there is a good chance that someone is going to kick down the doors to my palace sometime in the next 5 years and run a sword through me, sure I could spend a lot of time trying to figure out exactly how to increase the arable land in the northeast to drive up the peasantry’s corn yields, or I could take all of the money and mental energy that would have cost me and spend it creating the worlds largest bacchanal filled with drugs, prostitutes, and probably Dennis Rodman.18 Thus, the end of growth.

So, that’s roughly the first order argument for extractive institutions hurting growth. Why then should we expect institutional persistence. On one level, this is obvious; rare is the dictator who decides that actually they would prefer not to be one.19 Dictators can use their access to power and resources in one period to secure the continuity of that access into the future. Without some sort of change from outside the system, its hard to see why we should expect change.

A slightly more subtle point, I think, is that mainting the continuity of extractive institutions might directly require hurting economic growth. Suppose you are king and a bunch of peasants come to you and say:

“Hey, all of these high taxes are hurting our growth. If you reduce them, we promise to pay you a high enough percent of the benefits that you actually increase your income as well.”

On the one hand, this is great. You get to have your kingdom grow while keeping up your debaucherous spending of other peoples money. On the other hand, doesn’t it sort of sound like those peasants are up to something? How do you actually know that they will follow through on their promise; after all, once they have money it will be a lot harder to force them to give it up. They might spend some of it on swords or guns and try to resist you.

The issue here is that there is a commitment problem. Even if there are gains to be on both sides made from allowing growth, growth also affects the distribution of resources, which means, in effect, growth affects the distribution of power. If kings let growth happen they have no way of knowing that anyone who grows more powerful than them will keep up their bargain once they are on the other end of it. The sensible thing to do is to keep blocking new innovations and keep taxes high so that you don’t risk the merchants or, god forbid, the farmers themself getting uppity.20 21

Putting this together, whoever initially has power in a society (because of the initial arrangement of political institutions) has an incentive to create economic institutions that harm growth both to personally enrich themselves and ensure they remain in power into the future. Thus, we should expect growth to happen when there is some sort of exogenous shock to the political equilibrium that creates institutions more responsive to people who would benefit from growth.22

All of this theory, of course, also applies when the specific invention being discussed is the steam engine and therefore has tremendous implications for what type of state we would expect industrialization to emerge in.

II.B Reverse Uno Card

Of course, there are some reasons to think that the opposite might be the case. That is, that inclusive institutions might slow growth while extractive ones encourage it. I rarely see this argument made in historical contexts, largely because I think it is mostly implausible before the rise of the modern welfare state. The argument goes thusly: inclusive democratic institutions redistribute wealthy from the rich, who would invest it in productive innovations, to the poor who will consume it to improve living standards.23 Furthermore, this transfer occurs through a “leaky bucket” where administrative costs and incentive effects further reduce the efficiency of the economy.24 I generally am going to set this aside for this post, as with the time frames we are dealing with both in the real world and Middle-earth don’t really involve much redistribution from the rich to the poor.

II.C. All Your Favorite Papers Suck

So, what sort of evidence might we look at to see if the Extractive thesis is actually a good explanation for our questions?

We might start off by just looking at whether the persistence part of the thesis holds generally, rather than looking at the industrial revolution specifically.

That is, surveying the last millennia of growth, does the type of political institution in a country empirically explain whether it is rich or not. On the the surface level the correlation is fairly strong, however there are obviously a lot of confounding factors. For instance, there is a lot of literature that suggests the causality may even run the other way with economic growth causing democratization.25 26 27

So, researchers have generally adopted a lot of fancy empirical strategies to deal with these issues and try to isolate the causal impact of institutions on the economy.

There are a lot of papers on this.28 Like, an ungodly amount.29 Truly an unbelievable, astonishing, totally inconceivable amount of papers. Enough papers to drive you insane. Shub-Pulpaloth, eldritch god of paper, once gazed upon the amount of ‘Institutional Persistence’ empirical economics papers and felt its inhuman mind slip the reigns of reason.

And, for the most part, I don’t think these papers work; at least, I don’t think these papers demonstrate what they are trying to. That being that institutions persist over time and can therefore be assigned a heavy causal role in the explanation. My reason for saying this I am going to relegate to a long footnote, as the discussion is somewhat more technical and can be skipped by a casual reader.30 The general idea is that it is really hard to measure this sort of thing so broadly and most attempts have failed.

II.D Europe, Specifically

Another way of approaching the problem is to think about how this thesis relates specifically to the Industrial Revolution. That is, rather just trying to explain how the somewhat abstract concept of extractive institutions explains the even more abstract concept of general economic growth, we can investigate if there were specific differences in the institutions of the region the industrial revolution emerged in that allowed for invention, investment, and scientific discovery.

Let’s start by looking at Europe generally before narrowing in on England.31

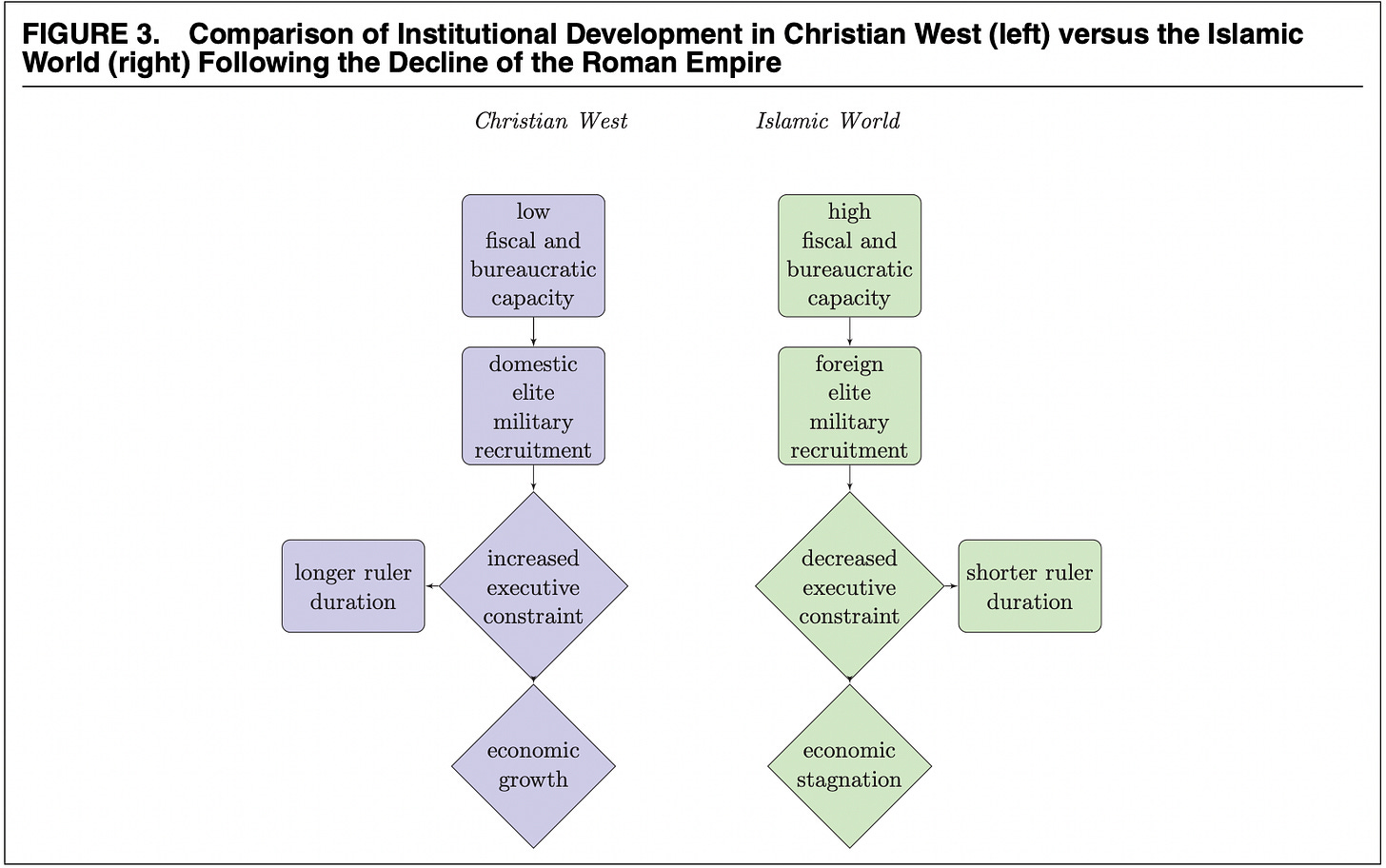

There were several differences between European polities and Middle Eastern and Asian ones. European kings were, on average, poorer than their eastern counterparts, more dependent on the support of lesser lords, controlled a smaller area, and were more likely to go to war with their neighbors.32

These things were often self reinforcing. One reason European kings were dependent on their vassals is because they were poor. Here’s a paper arguing that one reason parliaments and constraints on the power of a ruler emerged in Europe is that kings were too poor and disorganized to afford mercenaries and so were dependent on vassals to provide troops, who in turn demanded concessions.

At the risk of dramatically oversimplifying a millennium of history, I’m going to refer to this equilibrium of small, poor polities with constrained monarchs who are constantly at war with each other as the “feudal” equilibrium.

There are a few other insights as to how the feudal equilibrium might have shifted Europe away from extractive institutions earlier than elsewhere. For one, the constant competition between fragmented monarchs meant that there was pressure to avoid cracking down with onerous taxes on merchants, as they had plenty of outside options on places to do business. Indeed, Cox (2017) finds exactly this by pointing out that political fractionalization and parliamentary control are correlated with indicators of higher levels of trade and economic growth.33 Analogously, this fractionalization and warfare created heavy incentives not to crack down on intellectuals either, less your risk losing them to competitors.34

Merchants generally helped to constrain monarchs. Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (2005) argues that the rise of the Atlantic trade helped to shift the balance of power away from the landed elite and towards merchants, shifting the power equilibrium that in turn defined the institutional equilibrium.35 Shifting power away from the aristocracy may have been important, as we would expect them to use that power to preserve their station, likely blocking institutions that would have allowed for industrialization.36

II.E. England Specifically

If Europe was generally situated to restrain rulers from over extracting from their population, England on the brink of the Industrial revolution was perhaps at the forefront of this (at least compared to Prussia and France).

Specifically, England experienced significant political change that resulted in much securer property rights and less arbitrary economic interference from the monarchy. To breeze through the political history here, the king of England in 1688 prorogued (suspended) parliament and ruled by personal decree. This made many people very angry and has been widely regarded as a bad move.

Also he was catholic, which may have been an even worse move.

People were angry enough that they did a civil war, won, and replaced him with William and Mary. Importantly, the newly imported monarchs ascended to the throne conditional upon accepting fairly large institutional constraints on what they were allowed to do (Limits on taxation and debt issuance, prohibition on the king maintaining a standing army, bans on the king buying seats in parliament, parliamentary oversight of expenditure of funds, etc).37

The argument then, is that the “Glorious Revolution” which subserviated the king to parliament in many ways, helped to reduce extractive institutions by securing property rights, thus laying the ground for the Industrial Revolution in the coming century.

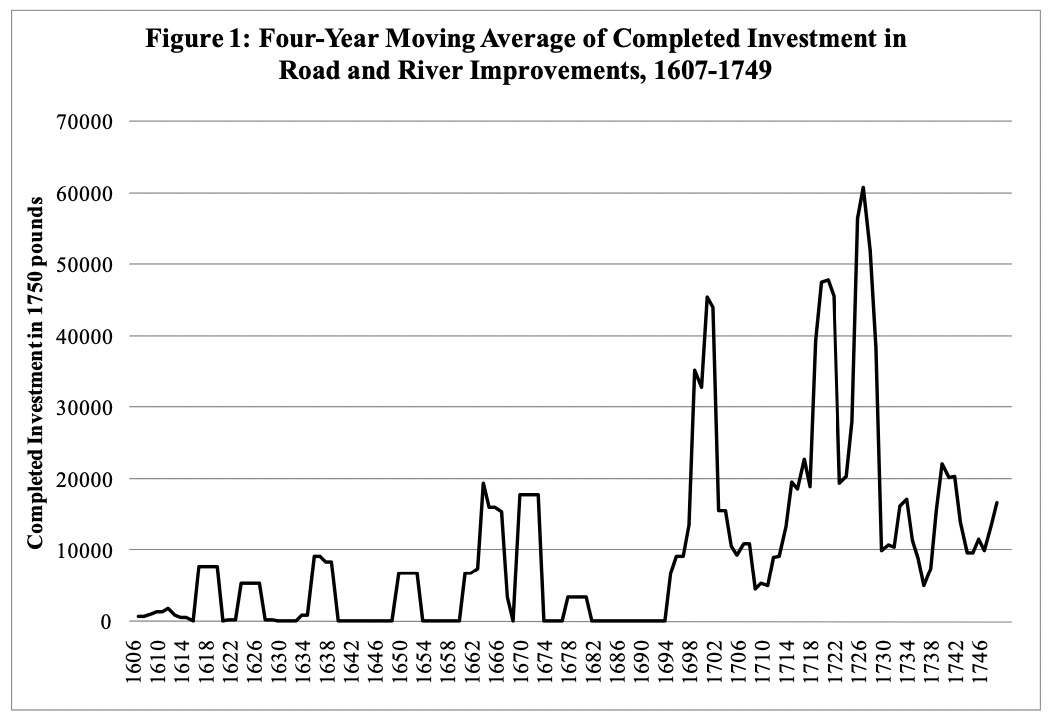

In general, there is some evidence that the Glorious Revolution increased the security of property rights. Private investment in road and canal infrastructure, which was somewhat notorious for being seized or disrupted by the crown, increased significantly in the period following the GR.38 39

It is worth noting that this isn’t a totally universal view, with some arguing that property rights had been secure prior to the Glorious Revolution.40 I generally land somewhere in the middle, with the GR being a large step forward in an ongoing process.

But, even if we don’t think property rights changed whatsoever, the Glorious Revolution absolutely marked a change in arbitrary interference by the monarch. As we’ll cover later, this mattered a great deal for peoples confidence in the government to do the things it promised, and leaves the more representative institution of parliament with greater power.41

Monarchical interference with politics had indirect spillovers onto the economy on top of extraction. As it happens, the government does occasionally need to do things to make an economy work. When the king and parliament fight about this, that basic work doesn’t get done.42 Following the glorious revolution, parliament was more successful at passing various bills establishing and simplifying property rights, allowing for economic growth.

So, England entered the 1700’s with a more constrained king, parliament more able to get work done, and potentially more secured property rights. But, in a somewhat interesting puzzle, that doesn’t mean that England began the Industrial Revolution with a weaker state. Rather, the contrary was the case.

II.F Dr. Sauron, or how I learned to stop worrying and love Tom Bomb

So, what of Middle Earth?

Obviously, Mordor is basically ruled out here; it’s entire population is either Orcs or literal slaves. If the person doing inventing isn’t named Sauron they are just going to get their new gadget yoinked immediately. As fortune has it, Sauron is pretty good at inventing, so it isn’t necessarily too much of a concern, but still is evidence that the overall population probably are not going to be making costly investments.

For Gondor, let’s start with comparing the material conditions against Europe.

Gondor relative to Europe appears to be faced with less competition and, specifically, less hostile competition. This is a somewhat odd statement to make given that the kingdom has what is basically the next door neighbor from hell. But, for roughly a millennia-ish before the war of the ring, Gondor really only had to deal with the the three successor states of Arnor as viable alternatives. The Shire existed of course, but was basically unknown (I think) while Mordor was dormant and not really a viable alternative for anyone looking for a place to live. Similarly, when Angmar was set up by the witch king it didn’t really seem like it was seriously competing for immigration or trade with Gondor.

Seemingly, this should allow Gondor greater room to maneuver with regard to extracting resources from its population. With few legitimate alternatives, merchants and peasants and inventors and what not don’t have the option of just leaving to set up shop elsewhere and thus should have to bear higher rates.

Of course, that’s just room to maneuver and isn’t the same thing as Gondor’s institutions actually being worse for growth. Here, I think the evidence is ambiguous. The little we know of the origins of “Aragorn’s Tax Policy” as the other R.R. likes to put it, is mixed.43

Effectively, the ruler of Gondor (King or Steward) is supposed to govern “according to ancient law” and is expected to consult with the Great Council of Gondor, which seems to be composed of most of the notable nobility, when making important decisions. Neither of these are directly constraints on the monarch. We aren’t told that the council gets a veto or that there is some court or judge who gets to decide if the king is in accordance with whatever this ancient law is, but that doesn’t mean that they are entirely toothless either.

Even if a monarch is entirely formally unconstrained, having unenforceable institutions that don’t directly bind a ruler can still result in less extraction and exploitation. The logic is thus: eventually if a ruler is bad enough, people will want to revolt and overthrow them. One of the big problems with doing a revolution is that it only works if everyone else does it as well. So, you want to be really confident that everyone else is going to turn up to the coup. Having big formal rules that a monarch disregards is basically like having giant neon flashing lights saying “everyone get your pitchforks out, its sedition time”.

If the great council told Denethor “Hey we actually aren’t cool with this invoice from the treasury asking for One Billionty Trillion Dollars to be spent on Pipeweed” and Denethor told them “Verily though bitches can sucketh it. For the Lord of Gondor is not to be made the tool of other men's purposes, however worthy. And to him, there is no purpose higher in the world as it now stands than the purpose of getting high”. That would be a pretty good sign that intervention is needed!

The takeaway here is that Gondor doesn’t seem to be in the best shape with constraining dictators, but it could also be a lot worse off. Forcing Kings (and maybe Queens, not totally sure what the succession rules are) to go through the motions still forces them to behave somewhat less they risk giving an obvious reason for people to get mad and revolt.

Overall, I would guess that Gondor is a fair bit weaker with protecting people from the state than early modern Europe, but it probably isn’t totally out of the question that people would feel secure enough to make investments in new businesses and technology.

III. State Capacity

So far we have told a very negative story about the relationship between politics and growth. Government, we have said, is largely bad and states succeed when the power of tyrants is constrained. This is kinda correct, but doesn’t give the entire picture.

States can do things other than frivol away taxes on the idiosyncratic whims of monarchs. They can, for instance, enforce laws and contracts. Both preventing murders and mediating disputes tend to be things we associate with better economies. Similarly, states can provide public goods that the private sector is unwilling or unable to provide. This ranges over quite a lot of economically beneficial areas from thousands of years of flood control in ancient Egypt to small modular nuclear reactor research at DARPA.44

Europe, and particularly England and France, saw significant growth in the size and capacity of their state apparatus from the 1500’s onwards that made them somewhat unique compared to the rest of the world. This, I’d argue, was another significant contributing factor to the Industrial Revolution.

Before looking at how the state caused the IR, it’s worth looking at what caused the state.

III.B Drivers of State Capacity

The first contributing factor to (and my preferred explanation for) Europe’s sudden rise in state capacity in the 1500’s is warfare. Specifically, changes in warfare.

Here is a brief model of how warfare might drive state capacity. This is largely pulled from Charles Tilly’s Coercion, Capital, and European States, albeit with some updating and modifications.

In post-Roman Europe, the continent was locked into the ‘feudal’ equilibrium. One way of explaining why this was the case is that the current military technology (castles, basically) made it relatively cheap to defend a small area against larger attacking forces. Overcoming these defenses required prolonged sieges or sophisticated battle tactics which were both expensive and required a large amount of coordination.45 As no rulers in Europe possessed the economic or logistical capacity to overcome the defenses of local lords, the continent experienced heavy diffusion of weak nobles. These nobles, due to their receiving revenue only from the lands under their immediate control and, for reasons we will discus later, being unable to borrow large sums of money, were never able to afford the military power needed to conquer the additional land needed to break this cycle.46

This changed in the 15th-16th centuries with the introduction of firearms, specifically artillery. Large guns provided a somewhat cheap and very effective way to blast down medieval fortifications, shifting the balance of power. To respond to this, Europe developed a new system for waging war and notifying defenses principally relying on the trace italienne style fort.

I’m not going to bother with the details of why here, but the effort and cost of this new military system was significantly higher than the previous (basically, because to have an effective fort now required moving a lot more rocks around).47

This, in effect, created an evolutionary pressure.48 49 Leaders who were unable to build a state apparatus that could coerce large amounts of manpower and/or finance from the population were overrun by those who could50 51 We might even take this one step further and argue that part of the reason we saw a shift in technology in the first place was because of how splintered and warprone Europe was. There is much greater pressure to attempt innovations in tactics and military technology if you face a real threat of annihilation if your neighbors do so first.52

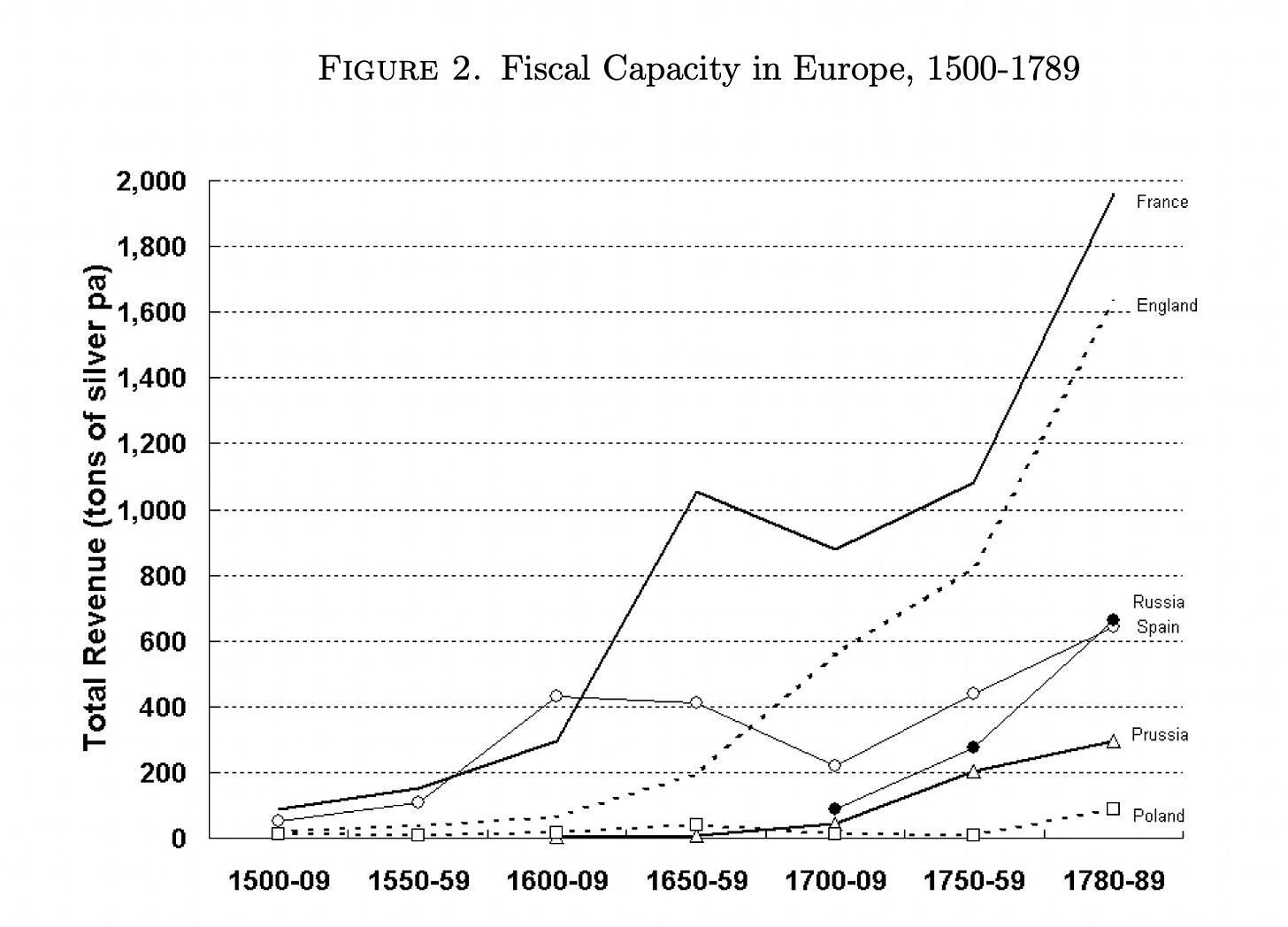

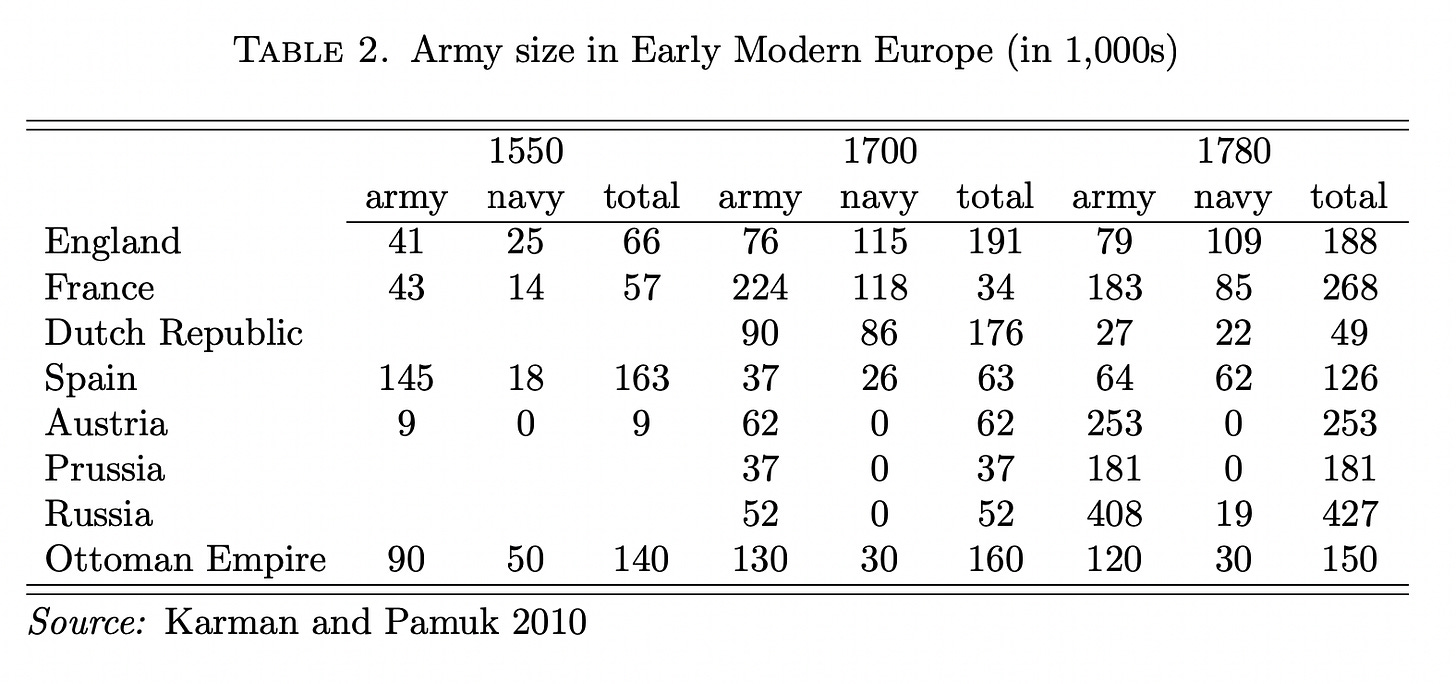

This theory holds up when we look at the change in sizes of armies post 1500:

As well as how wealth affected the odds of winning wars:

The interesting thing here, for our purposes, is how leaders coerce resources, because the apparatus that lets one acquire increased taxation also serves as a general purpose statebuilding tool.53 That is, even though a bureaucracy and tax system might be created for the purposes of war, it doesn’t go away after the fact. Indeed, the exogenous shock of new war technology results in permanently significantly higher amount of state capacity.54 55

Of course, the exact mechanisms by which rulers created states varied according to local institutions and the final outcomes varied as well.56

An interesting test of this hypothesis can be found here. The authors find that more war casualties in the 18th century were correlated with higher taxation and that in turn is correlated with modern day economic performance (controlling for a fair amount of other factors).57

And over the very long run this theory seems to bear out.58

Outside of warfare, it is worth noting that Europe may have started with a bit of an advantage anyway. The existence of the christian church is somewhat unique as a persistent international organization that has lasted for over a thousand years.

The various apparatuses of the state: courts, the rule of law, clerks and notaries and so on, began to emerge during the Middle Ages. A large reason for this is the separate and distinct entity of the church. The foundations of secular legal systems in Europe are directly pulled from pre-existing roman (read “religious”) law. The church served as the main source of educated bureaucrats when otherwise illiteracy predominated and brought with them pre-existing templates of administrative organization from the church that they then spread to secular polities. Plausibly, the relative uniqueness of the “NGO” of the Catholic Church is yet another explainer for early European growth.59

Finally, the rise of the European town and the merchant class provided an alternative source of income for the state that reduced dependence on the landed nobility whereas in previous time periods it would have been much harder to consolidate power away from them.

III.C Sidebar

As a sidenote, it is worth suggesting that state capacity and ruler constraint are not necessarily antagonistic. Part of the rise of more sophisticated legal systems can be explained by elites demanding more formalized rules about what exactly a ruler is and is not allowed to do.

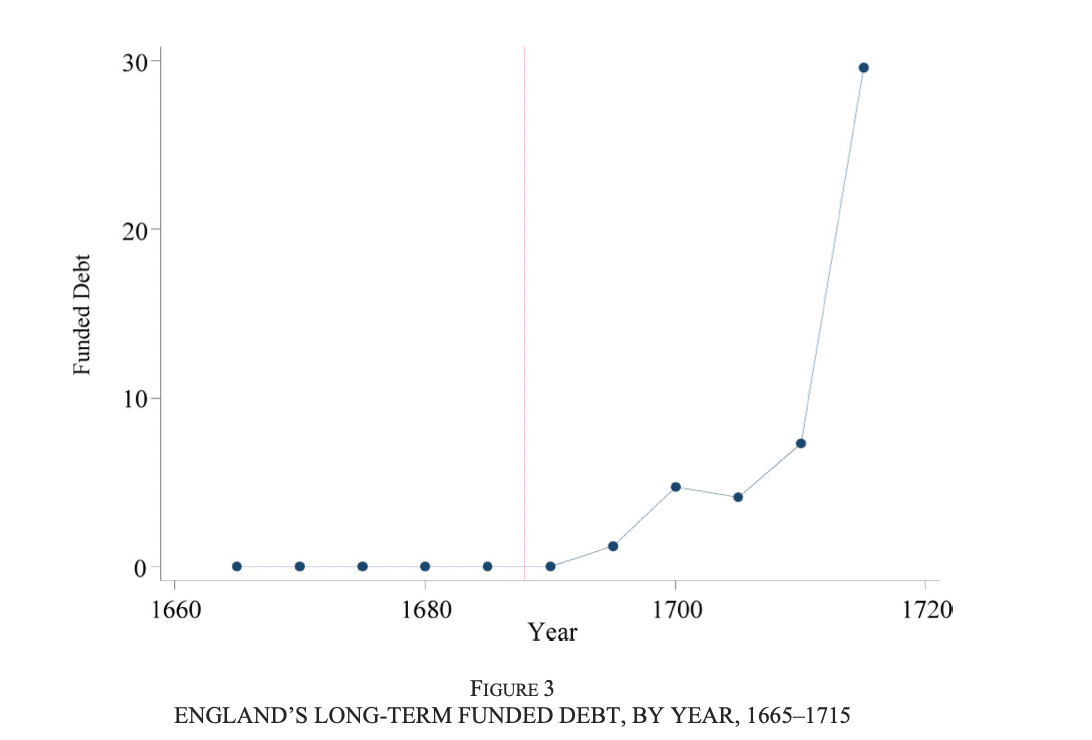

Lots of the papers cited above also show that political constraints and representative institutions actually increased state capacity. Indeed, after the Glorious Revolution gave parliament more power to ensure funds were not misspent, total tax revenues went up significantly.60

And (potentially) the increased dependability of the British Government may have allowed it to borrow significantly more funds as lenders would be more confident in being paid back.

This may not have been universal however, one common argument is that the direction of the interrelationship between state capacity and constraints on a ruler is actually dependent on what type of economy a polity has. The logic here is that in an agrarian economy state capacity is built by crushing local feudal elites to take their local tax revenue and redirect it to the state. Because there is no sophisticated commerce going on, there is no need to worry that this top down authority will discencintivize commerce.

Alternatively, in urban-commercial economies like The Netherlands or England the revenue needed to build up state capacity is going to be siphoned off of merchants, bankers, and the like. In this case, representative institutions help to build state capacity by limiting the downside effects of uncertainty about expropriation.61

III.D. Capacity and the Industrial Revolution

So, what did states do with their new found administrative capacity that encouraged growth. Particularly, how did it result in the industrial revolution.

In part, this is simply the mirror of our argument about how oppressive governments hurt growth. Just like I might not bother spending time and resources on investment if the king might take it, I probably also won’t bother if I think it’s likely a roving band of thugs will get together and take all my money. To borrow from Bakunin “When the people are being beaten with a stick, they are not much happier if it is called "the People’s Stick". The state, when working correctly, provides significant protection against this sort of expropriation.

In general, at least when looking at the modern day, the income (as a proxy for capacity) of a state does seem to vary with property right protection.62

Second, the state can engage in investments like encouraging market development or building infrastructure that can help growth. This can even be self reinforcing as states with a high capability to tax have an even larger incentive to invest in growth enhancing investments. We covered this briefly above with the example of the state better protecting transport infrastructure investment.

In the case of Britain, the greater administrative capacity of the state not just allowed for greater protection of property rights, but also better property rights.

One place institutions exhibited the property of just sort of being not that great prior to the Industrial Revolution is figuring out who owned stuff. At first encounter with the idea, I found this very strange. In the modern day its pretty clear who owns things even if we dispute whether or not they should. More specifically, if I own something we have a pretty good idea of what that means: I can sell it, transfer the property to someone else, rent it out etc. Ownership implies a general bundle of rights that all go together.

In preindustrial Britain this was very much not the case. Ownership did not necessarily imply the right to sell a property and may in fact entail obligations to rent it at specific prices to specific people for specific amounts of time. This emerged, essentially, through centuries of complex agreements and social arrangements that persisted as legal systems became more developed. It also was a massive headache.63

In the century or so prior to the IR, the English state intervened and generally simplified property rights to allow for significantly more flexibility, clarity, and easier transfer, allowing for more efficient employment of land and resources. As mentioned in the above sections, a very plausible explanation for the increase in this activity is parliament’s increased ability to set its own agenda and schedule post GR, but that doesn’t fit perfectly with the timing (as you can see below).

The state’s involvement in property rights continued with the invention of new property rights, specifically: patents.64

Patents, generally, grant a monopoly over use of a certain invention to its creator for a certain period of time. This generally is an attempt to strike a balance between incentivizing innovation and allowing for the invention to be adopted be other firms. Patents also serve as an important distributer of knowledge, as to receive one requires public disclosure of a fair amount of details about how your invention works.

Of course, its difficult to provide definitive evidence that the industrialization wouldn’t have occurred without the rise of the patent system, and the evidence is certainly complicated, but it seems more than reasonable to assume they played some part in inducing invention.65

III.E. Some Pun About Gondor I’m To Lazy To Think Of Right Now

What then, should we take from this to look at Middle-Earth?

Gondor at the end of the third age is a semi-constitutional monarchy where nobles have some input on the government.

A Númenórean King was monarch, with the power of unquestioned decision in debate; but he governed the realm with the frame of ancient law, of which he was administrator (and interpreter) but not the maker. In all debatable matters of importance domestic, or external, however, even Denethor had a Council, and at least listened to what the Lords of the Fiefs and the Captains of the Forces had to say.66

The actual capacity of the state to do things is curious. I think the easiest way to examine Gondorian state capacity, given we don’t have revenue figures, is to look at how Gondor sources and pays its military. One the one hand, the army appears to operate largely on the basis of feudal obligation. While certain “companies” do appear throughout the text, this seems to be to used to denote a separate small professional core distinct from the average soldier. Furthermore, assuming Tolkien is deliberate in his use of “knight”, we receive pretty direct evidence of this (knights being a very feudal title).

This seems to put the kingdom of Gondor’s administrative and fiscal resources somewhere above a standard feudal kingdom given its ability to direct manpower and maintain standing forces but below a sophisticated early modern or ancient army. Gondorian administrative capacity more generally is again an open question. Clearly it can raise sufficient funds to maintain a beacon warning system and several capital intensive fortifications, but the question of the states overall revenue raising and expenditure ability is questionable.

I think this makes sense given Gondor’s historical position. The state has not regularly been forced into wars that require the development of a bureaucracy for survival. The northern splinter kingdoms were much smaller states individually than Gondor and the large armies from Angmar and Mordor are a recent phenomenon rather than an ever-present historical phenomenon that Gondor would have adapted to.

A side effect of this is that Gondor does seem very medieval in how it treats property. Rights to land and rule seem to be culturally treated as if they translate generationally and appear difficult to alienate or transfer. Obviously, the lack of bureaucrats (I would note once again, how much the lore masters of Minas Tirith suck at literally their only job) suggests patents are not an option. More generally, the weakness of the Gondorian state leaves any merchant class open to large amounts of predation by bandits and local lords.

Mordor, of course, seems to possess an enormous amount of state capacity, what with it being an authoritarian nation-state ruled by a magical dark lord for two and half millennia and all.67 However, this emerges in practice as control over large amounts of manpower (Uruk-power?) rather than any sophisticated financial system or deep bureaucracy. While the Witch King seems to be a relatively competent commander, the fact that Sauron’s government is basically run by 9 malevolent shadows who couldn’t manage to find and capture a, lets be honest, basically incompetent hobbit living in a famous house named after himself for like 50 years because they didn’t even know the entire country of the shire existed, does not speak well to the organizational capacity of the Mordorian state.

In fact, these Sauron having access to slavishly loyal troops and Mordor’s state power being somewhat low almost seem related. The relative ease with which Sauron can command the forces of darkness means he doesn’t have any need to develop sophisticated systems of taxation or state power. In fact, Mordor’s capacity outside of troop mustering is so weak that they’ve outsourced a good 40% of homeland security to an independent contractor (who happens to be a giant spider).

Mordor, I think, makes a bit less sense than Gondor. There aren’t any local lords or notables to oppose Sauron constructing a much more organized state than he has and Mordor definitely would benefit from like, an accountant or two.

Plausibly Sauron is too much of control freak to delegate? If your grand design is to assert your personal will over the universe to bring order to it, it would be a bit inconsistent to have a personal assistant who like, handles your schedule.

IV. Return of the Bling

Another place institutions intersect with growth, and the last I’m covering in this post, is in finance. We’ve covered this briefly when we discussed how England was able to raise more money after placing constraints on the sovereign, but it is worth covering in more depth.

Finance, generally, can be thought of as doing two things. First, it is a technology that allows people to transform risk. If I loan out my 10 dollars in the hopes that I get paid back with interest later, then, effectively, I have paid 10 dollars in exchange for some probability of receiving 10+X dollars back at some point in time. The ability to make these sorts of transformations is utility enhancing by itself. Different people have different preferences over risk, and being able to trade risk is useful. For the most obvious example of this, consider health insurance.

But the true long-run benefit of finance to growth is that it helps to solve capital constraints. Imagine it is the year 1800 and I come up with the brilliant idea of cheap mass-produced indoor plumbing. Problematically, I have no money with which to open up a plumbing shop or pay employees. Even though I have all the science and engineering figured out, I have no way of turning that into a material effect on the world. The solution here is to borrow money. As long as the interest rate is below the return I expect on the investment, I still come out ahead on the business. The insight here is, all else equal, that the more loanable funds available and the cheaper they are, the more businesses we should expect to start up.

Of course, finance isn’t something that is ever present across time. For one, as demonstrated by certain Bahamian crypto derivative companies, running financial institutions requires a great deal of expertise. But there also need to be institutional systems in place that support it, the government is a significant player in bond markets and, in modern times at least, regularly intervenes in and regulates many other financial markets to support the ecosystem.

IV.B. Financing Revolutions

Of course, the story of finance and the IR can be more complicated. If the sorts of people who start business are already rich or businesses have relatively low start-up costs, then the availability of finance isn’t that important. As such, its worth reviewing both the change in the supply of finance before the IR, as well as if there was actually any need for it.

Lets start by looking at the British government. The story North and Weingast, the authors of the canonical paper on it, want to tell is that following the Glorious Revolution the increased stability and trust in the government lowered the borrowing rates on British debt (because the king could no longer just stop paying it). This then spilled over into the private market. As government debt became stable, institutions rose to deal in the secondary market for these bonds. As these businesses operated, they developed financial expertise in how to handle risk and banking that could be applied in other areas as well.68 Thus, this initial change in the governments finance provided the infrastructure needed for a much broader financial system. Additionally, the increased stability decreased the likelihood of any sort of negative contagion throughout the financial system and may have attracted new investors to the market.69 This was all made even more potent by the contemporaneous establishment of the Bank of England, who would shortly begin to act as a lender of last resort, stabilizing financial markets even further.70

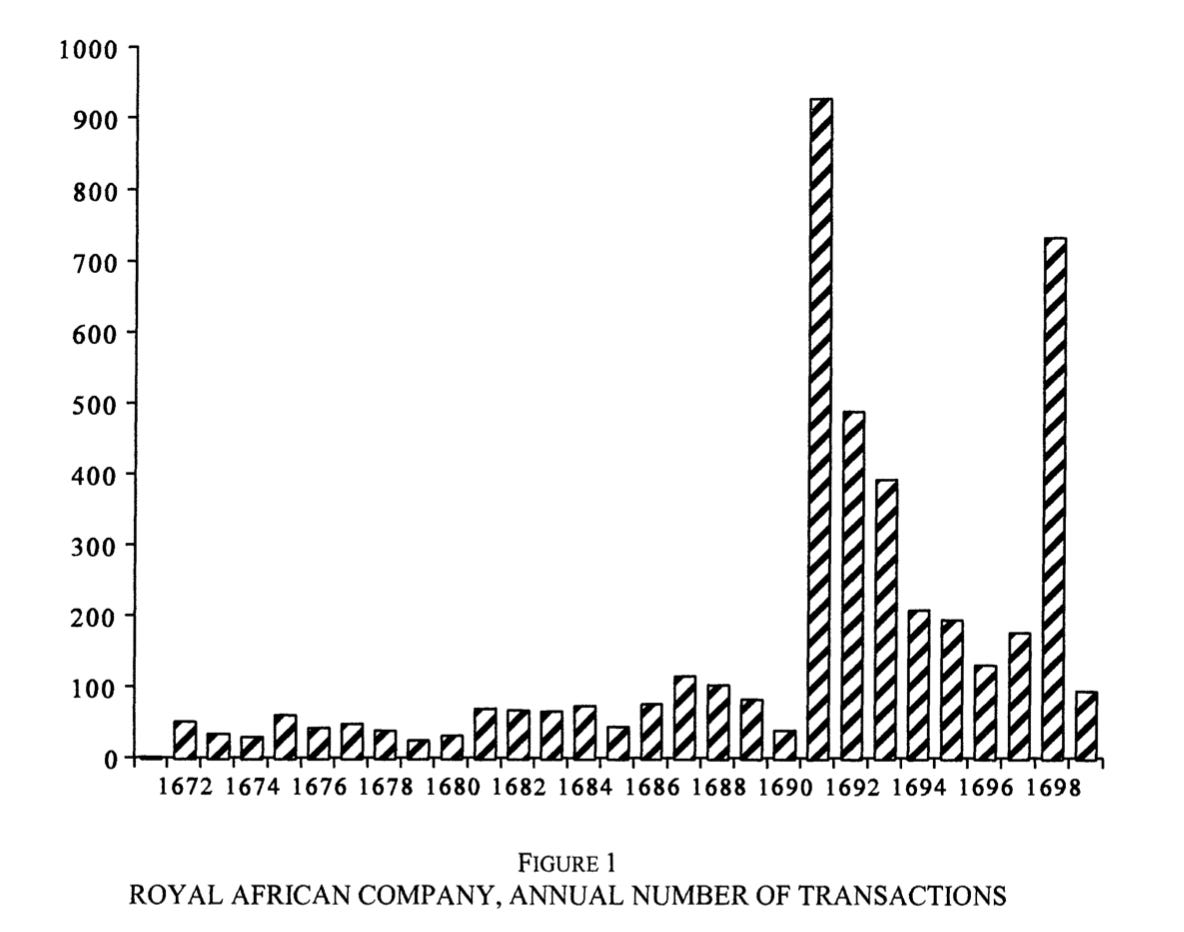

There is some initial evidence for the thesis, various measures of private financial activity such as the volume of private securities spiked following the Glorious Revolution and the interest rates on private loans fell.71 72

On the other hand, cheaper and more stable government bonds could have actually depressed the financial system by drawing investors away from the private market.

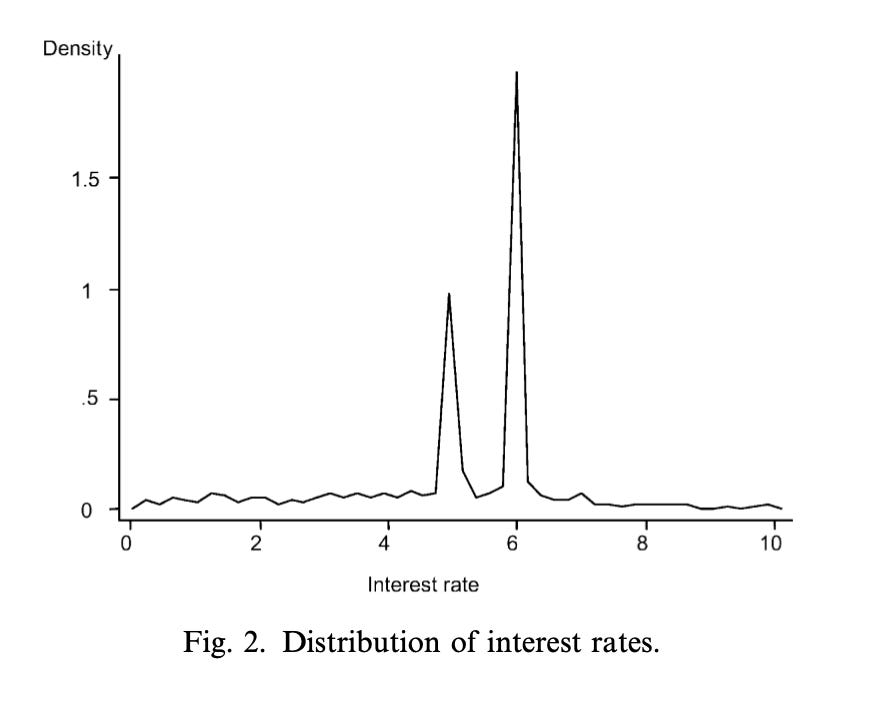

When we look at individual data for a private lender at the time, private interest rates actually rose during the period following the Glorious Revolution, indicating either that we didn’t see the sort of spillover from the public market or that this was outweighed by a large increase in demand. This isn’t evidence that the Glorious Revolution didn’t increase supply of finance, just that the evidence we do have is ambiguous.

An additional complicating factor is that even if the threat of government default was lessened, there were still other significant institutional impediments to the supply of finance. Specifically, England, along with most of Europe, imposed usury restrictions that limited the interest that could be charged on loans.

When we look at data on loans made in the post-GR period, a vast majority are made at the usury limit, suggesting that supply didn’t expand not because it became cheaper to make loans, but that the reduction in cost didn’t matter because the limit was still too low for the reduction to have come into effect.73

There were some fun ways to circumvent these restrictions, but, as shown above, they did impede the free flow of finance significantly.74 Of course, usury restrictions were not a permanent facet of life and as they fell away over the course of the next two centuries, the more stable base allowed for the growth of the financial system.

So, the expansion of the amount of finance supplied was initially questionable (though rose in the long rung), but where and how that finance was supplied may have changed. And, this matters quite a lot.

Britain was somewhat unique in that it possessed an extensive network of regional branch banks extending out in a network from London. This was helpful for industrialization in several ways. First, banking in an era with significantly less information tended to rely on personal connections and social relationships to form trust in place of sophisticated contracts. A regional network means a wider amount of people are covered in this. Something that is especially important given that early industrialization began outside of the capital.

Second, for reasons I won’t bother getting into (I have been working on this post for so so long and am so so tired of it), these banks behaved in many ways like venture capital firms with heavy amounts of investment into nascent industries. Empirically, we have evidence that these banks lent heavily to mining operations to allow them to borrow to purchase new steam engines, suggesting that at least somewhat finance was needed to allow new industries to take off.75

IV.C. The Curious Incident of the Smaug in the Knight-Time

So what does the financial system look like in Middle Earth?

On the bright side, no Christianity means no usury restrictions.

On the not so bright side, finance doesn’t seem to exist.

In large part, we have no evidence of any sophisticated financial system. The word “bank” is only used to refer to riverbanks. Loans do appear to be a concept some people are familiar with, as Gandalf asks for a loan of Shadowfax from Theoden.76

“‘But as for your gift, lord, I will choose one that will fit my need: swift and sure. Give me Shadowfax! He was only lent before, if loan we may call it. But now I shall ride him into great hazard, setting silver against black: I would not risk anything that is not my own. And already there is a bond of love between us.’ “

I think we can also conjure up somewhat of a proof by negation.

After all, we do have textual evidence of at least one large concentration of currency, controlled by someone with a preternatural ability for accounting who, as it happens, did “not have much use for all their wealth, but they kn[e]w it to an ounce as a rule, especially after long possession”. Furthermore, this person has perhaps the greatest means of insuring loan repayment available, on account of their being a 60ft long fire-breathing flying lizard.

A reasonable objection might be made here that even if Smaug is well suited to banking, he may not personally have a taste for it and, even if he did, who on earth would take a loan from a dragon? But, when you stop to think about it, Smaug is solely focused on having as much gold as possible and is seemingly able to do most of the calculations necessary to run a rudimentary lending operation, it really does seem like a perfect fit.

And on the point of no one taking loans from a dragon, perhaps because of his past history of bad behavior, I don’t think real world evidence suggests that people will hold grudges over historical conflicts when it comes to finance. Countries that went to war with each other just a generation in the past lent each other money all the time! This still happens! And its not like there is some sort of sophisticated international order that is going to embargo Smaug. The simpler explanation here is that finance as a business is just not really present in Middle-earth not that Smaug is some weird outlier.

We also get some evidence that even informal lending is not common. Consider a passage early on in LOTR where two hobbits discus Bilbo Baggins’s wealth:

But the Gaffer did not convince his audience. The legend of Bilbo’s wealth was now too firmly fixed in the minds of the younger generation of hobbits.

‘Ah, but he has likely enough been adding to what he brought at first,’ argued the miller, voicing common opinion. ‘He’s often away from home. And look at the outlandish folk that visit him: dwarves coming at night, and that old wandering conjuror, Gandalf, and all. You can say what you like, Gaffer, but Bag End’s a queer place, and its folk are queerer.’

‘And you can say what you like, about what you know no more of than you do of boating, Mr. Sandyman,’ retorted the Gaffer, disliking the miller even more than usual. ‘If that’s being queer, then we could do with a bit more queerness in these parts. There’s some not far away that wouldn’t offer a pint of beer to a friend, if they lived in a hole with golden walls. But they do things proper at Bag End. Our Sam says that everyone’s going to be invited to the party, and there’s going to be presents, mark you, presents for all – this very month as is.’

What I think is noteworthy here is that, in the process of discussing a local notable with wealth, neither Hobbit pauses to entertain that lending that money out is a way of adding to one’s fortune. Bilbo can only add to his money through adventuring, rather than simply doing business from where he is. Similarly, no discussion of financial instruments or loans outstanding appears in the following pages discussion of the distribution and ransacking of Bilbo’s estate.

Thus, contrary to what we see in the British case, personal ties and social networks do not seem to result in financial flows. And, I would note, this is in the Shire, a place which has incredibly dense social connections and appears to be well ahead of the rest of Middle Earth when it comes to institutional strength.

Assuming that this is not due to the eccentricities of Mr. Baggins, it is, I think, a very minor but real error in world building.

V. Conclusion

Often, when reading a post investigating some interesting bit of world building in a work of fiction, upon reaching the end the author will reveal that actually they had been secretly teaching you about something of great importance to our much more concrete and tangible world and, in fact, you ought to take this newfound knowledge and do something with it.

I assure you that is not the case here.

Much as Frodo journeyed through through unnecessary danger to get to Middle-earth’s largest garbage disposal, you too have journeyed through 10,000 words to find the answer to the question: Is Tolkien’s economic worldbuilding accurate?

To which I say “Eh, B+?”

Like, its basically fine. It doesn’t really emerge as a major theme in the books and that’s okay. I’m not entirely sure that Gondor is at a stable equilibrium with its political institutions and it seems ripe for fairly large internal conflicts if the line of Aragorn ever spits out a bad egg, but that’s not really an inconsistency in logic, just a problem for Gondor within the work.

It’s sort of weird that no one has figured out there is money to be made by opening a bank, but like, banks as we know them now weren’t exactly a thing for most of history. And maybe banks just aren’t mentioned! If I had to pick one point to harp on as weird it would be this one. Lots of armies and ventures and whatnot are raised throughout the book with relatively little consideration of where the money to achieve that is coming from. They use coins in the book, someone has to be printing them! Why haven’t they followed that up with any more sophisticated instruments.

Setting that aside, compared to the last two posts, I think the the institutions of Middle Earth make a lot of sense for a world that hasn’t industrialized.

The short version being that I felt kinda weird doing an extended bit where I engage in useless nitpicking about realism in Middle Earth while a bunch of people got mad at the new series for being “unrealistic” for having Black people in it and then kinda forgot about this post for a couple months

My return also has to do with the fact that people keep stealing my bit: https://pricetheory.substack.com/p/economics-in-the-lord-of-the-rings

Though Hobbits maybe are? Hard to tell

Yes I am aware that LOTR can be considered a thoughtful meditation on the horrors of World War I

To be clear, I am aware there is no National Bank of Gondor; they obviously have a freebanking system.

http://amechanicalart.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-lord-of-rings-as-pastoral.html

https://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/Downfall_of_Númenor

Although, I think we might make a case that this was a cultural issue and that any set of political institutions could have ended the same way

“Absurd” as in ridiculous, not as in “undeserved”

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2013). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Business.

Fukuyama, F. (2012). The origins of Political Order. Profile Books.

This is sort of muddle by the fact that a lot of institutions research suggests a lock in effect where early institutions determine later ones, but I think institutions are still percieved as more changeable than other factors

I recognize that this is a fairly bleak Hobbesian view of the world, but 1. I think its just correct. 2. IDK it’s kinda nice to think that the reason we have human rights and stuff is that a lot of people agree it’s important

I am using Why Nations Fail as a shorthand for the array of papers and articles by Acemoglu, Robinson, and Johnson

For simplicity, I’m just going to use a dictator as shorthand for extractive institutions. Of course, in the real world they can take many forms.

More technically, consider that the king is a rational utility maximizer whose utility is determined by the function U = F(t,p) where t is the tax rate and p is total production in the economy. Let us also assume that pis decreasing with respect to t so that as t goes up producers reduce their output. The king is going to select a tax rate t such that it maximizes U which will be where dU/dt equals 0 (standard assumptions about no corner solution made). Assuming that the relationship between t and p is such that a tax rate of zero does not maximize utility (which is obviously true because then the king would have no money) the king is setting a tax rate above what maximizes production.

Olson, Mancur, 1993. "Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development," American Political Science Review, Cambridge University Press, vol. 87(3), pages 567-576, September.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dennis_Rodman#North_Korea_visits

Off the top of my head I can think of like Cincinnatus, George Washington, and maybe Olusegun Obesanjo

Acemgolu (2003). “Why not a Political Coase Theorem? Social Conflict, Commitment, and Politics,” Journal of Comparative Economics 31, pp. 620-652.

Acemoglu and Robinson (2000). “Political Losers as a Barrier to Economic Development,” American Economic Review 90 (2), pp. 126-130.

Institutions As the Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Economic Growth, in Handbook of Economic Growth, editors Philippe Aghion and Stephen Durlauf, North Holland, 2005.

Sen, A. (2000) ‘The Importance of Democracy’ in Development as Freedom (New York: Anchor Books) 146-159. JC585.SEN

Arthur M Okun. Equality and efficiency: The big tradeoff. Brookings Institution Press, 1975.

Przeworski, A. et al. (2000) Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and wellbeing in the World. 1950-1990

Boix, C. and Stokes, S.C. (July 2003) ‘Endogenous Democratization’, World Politics, 55(4), 517-549

Ansell, B. and Samuels, D. (2014) ‘Economic Development and Democracy’, Annual Review of Political Science, 9, 503-527

Acemoglu, D. et al. (2104). ‘Democracy Does Cause Growth.’ NBER Working Paper Series.

Engerman, S.L. and Sokoloff, K.L. (2008) ‘Debating the role of institutions in political and economic development: Theory, history, and findings’, Annual Review Of Political Science,

Glaeser, E.L., La Porta, R., Lopez‐de‐Silanes, F. and Shleifer, A. (2004) ‘Do institutions cause growth?’, Journal Of Economic Growth, 9(3), 271‐303

Rodrik, D., A. Subramanian and F. Trebbi. (2004). “Institutions Rule: The Primacy of Institutions over Geography and Integration in Economic Development.” Journal of Economic Growth 9(2):131–165.

Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (2001). “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation” American Economic Review 91 (5), pp. 1369-1401.

Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (2002). “Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World Income Distribution” Quarterly Journal of Economics 117 (4), pp. 1231-1294.

Dell (2010). “The Persistent Effects of Peru’s Mining Mita” Econometrica 78 (6), pp. 1863-1903.

Nunn and Wantchekon (2011). “The Slave Trade and the Origins of Mistrust in Africa” American Economic Review 101 (7), pp. 3221-3252.

Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (2016). “The Long-Run Effects of the Scramble for Africa” American Economic Review 106 (7), pp. 1802-1848.

Banerjee and Iyer (2005). “History, institutions and economic performance: The legacy of colonial land tenure systems in India” American Economic Review 95, pp. 1190-1213.

Feyrer and Sacerdote (2001). “Colonialism and Modern Income: Islands as Natural Experiments” Review of Economics and Statistics 91 (2), pp. 245-262.

So, all institutions papers are bad is quite a strong claim I know. Before we begin, I should note that not all papers have the exact same problems and that I am discussing common themes I’ve seen in them. Your favorite paper may not have these exact issues (though I would probably bet money it does). For an even more comprehensive look at the problems with the institutional persistence literature I can’t recommend this four part series by economist Dietrich Vollrath enough.

So, the problems with the literature. First, a great many of these papers use an instrumental variable approach to institutional effects. Almost invariably, the idea that these IVs actually comply with the exclusion restriction doesn’t pass a smell test. If the IV doesn’t work, the analysis basically goes out the window.

Second, most of the papers try to operationalize institutions using something like Polity Scores or the equivalent. This has several problems. 1. These scores are usually categorical in nature, but get treated like continuous variables. 2. If you really unpack how these scores get made, they often are looking at outcomes rather than institutions. 3. There is a lot of arbitrariness that goes in to the coding of these variables that makes cross national comparison dicey.

Third, even if you buy all of the empirical results, most of these papers just show persistence, not institutional persistence. If I have a paper that proves there was an exogenous change in institutions that caused persistently lower economic growth. That doesn’t prove that the reason growth stayed low was because of institutions the entire time. Its also consistent with the idea of poverty traps and the like. Maybe negative shocks of any sort (not just institutions) have a persistent effect for various reasons.

Fourth, I can’t prove this for every paper obviously, but a lot of historical Econ papers have just absolutely atrocious citations when it comes to the historical side of things. This isn’t necessarily a reason to distrust the empirics, but I think it should make you suspicious.

Fifth, when a paper isn’t using an IV strategy it’s almost always a cross-national regression. I think cross-national regressions on stuff like economic growth is basically useless because there are almost never appropriate controls used.

I should, given we are about to discuss the roots of Europe’s comparatively earlier growth, note that political institutions causing economic growth is not necessarily evidence of moral superiority. Moreover, just because ones country took off earlier is not a good reason to think that country currently contains people of more moral value.

Tilly, C. (2015). Coercion, capital, and European states: Ad 990-1992. Blackwell.

Cox (2017). “Political Institutions, Economic Liberty, and the Great Divergence,” Journal of Economic History 77 (3), pp. 724-755.

Joel Mokyr (2017) “How Europe Became So Rich.” Aeon, February 15

Of course, same IV caveats apply here

Acemoglu and Robinson (2000). “Political Losers as a Barrier to Economic Development,” American Economic Review 90 (2), pp. 126-130.

COX, G (). Was the Glorious Revolution a watershed? Journal of Economic History , pp.–.

BOGART, D (). Did the Glorious Revolution contribute to the transport revolution? Evidence from investment in roads and rivers. Economic History Review , pp. –.

Besides just being evidence of property rights being secure generally, transportation is an important sector in and of itself as increased investment lowered costs allowing for firms to have a wider market and therefore accumulate more capital. Plausible something that was important for the IR.

Bogart, Dan. "Did turnpike trusts increase transportation investment in eighteenth-century England?." Journal of Economic History (2005): 439-468.

HODGSON, G (). 1 and all that: property rights, the Glorious Revolution and the rise of British capitalism. Journal of Institutional Economics , pp. –.

GregoryClark(1996 “The Political Foundations of Modern Economic Growth, England 1540- 1800.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History

MURRELL, P, Design and Evolution in Institutional Development: The Insignificance of the English Bill of Rights, working paper, ().

Still not that representative

Bogart, Dan, and Gary Richardson. "Property rights and parliament in industrializing Britain." The Journal of Law and Economics 54.2 (2011): 241-274.

https://www.tolkiensociety.org/2014/04/grrm-asks-what-was-aragorns-tax-policy/

Hoffman, Philip. 2015. “What Do States Do? Politics and Economic History.” Journal of Economic History 75(2):303-332.

If you want to counter this by pointing out the arrival of empires like the Carolingians or the Holy Roman Empire, consider that these were more loose amalgamations of local lords with feudal obligations in a pyramid structure than examples of a monarch directly controlling large areas.

Parker, Geoffrey, 1943-. The Military Revolution : Military Innovation and the Rise of the West, 1500-1800. Cambridge ; New York :Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Hendrik Spruyt, “Institutional Selection in International Relations: State Anarchy as Order,” International Organization (1994), 48:527-557

Brian Downing (1992) The Military Revolution and Political Change

Boix, Carles War, Wealth and the Formation of States. . In Norman Schofield, ed. Political Economy and Institutions, Springer-Verlag. 2009

Empirically, more fiscally capable powers became increasingly likely to win wars.

Nicola Gennaioli and Joachim Voth (2013) State Capacity and Military Conflict

Thompson, William R.; Rasler, Karen (1999). "War, the Military Revolution(s) Controversy, and Army Expansion: A Test of Two Explanations of Historical Influences on European State Making". Comparative Political Studies. 32 (1): 3–31

Tilly, C. (2015). Coercion, capital, and European states: Ad 990-1992. Blackwell.

As a note: This is a simplified model; initial firearm adoption was probably not a purely random event.

One explanation is that a labor shortage post Black Death led rulers to substitute military capital for labor.

See: The Black Death and the Transformation of the West

Some arguments agree with the warfare hypothesis but move the date back earlier to the medieval period.

Blaydes, Lisa., and Christopher Paik. (2016). “The Impact of Holy Land Crusades on State Formation: War Mobilization, Trade Integration, and Political Development in Medieval Europe,” International Organization 70 (3): 551-586

Even more extreme views argue for path dependence in state capacity dating back to c. 3,000 b.c. Borcan, Oana, Ola Olsson, and Louis Putterman. "State history and economic development: evidence from six millennia." Journal of Economic Growth 23.1 (2018): 1-40.

An interesting challenge to this theory is why, if war makes states, has this not been true outside of Europe? Plenty of developing countries have been exposed to war and not seen the same sort of result. The answer here, I think, is timing. Europe’s wars were during a period where taxation and more state capacity were the only way to raise funds. More recently, with the globalization of finance, states can borrow instead of taxing to finance their wars. Loans are politically easier for elites (they don’t have to take anyones money), but this doesn’t require the same level of intensive capacity building.

Queralt, Didac. 2018. “The Legacy of War on Fiscal Capacity.”

Centeno, M.A. (1997) ‘Blood and Debt: War and Taxation in Nineteenth-century Latin America.’ American Journal of Sociology, 102(6).

Dincecco, Mark and Mauricio Prado Warfare, Fiscal Capacity, and Performance Journal of Economic Growth, vol. 17, pp. 171-203, 2012.

Timothy Besley and Torsten Persson (2011) Pillars of Prosperity

Beyond War and Contracts: The Medieval and Religious Roots of the European State, Annual Review of Political Science, 2020. pdf

COX, G (). Was the Glorious Revolution a watershed? Journal of Economic History , pp.–.

Karaman, Kivanc and Pamuk, Sevket. “Different Paths to the Modern State in Europe: The In- teraction Between Warfare, Economic Structure, and Political Regime” The American Political Science Review. (2013)

Timothy Besley and Torsten Persson (2011) Pillars of Prosperity

Bogart, Dan, and Gary Richardson. "Property rights and parliament in industrializing Britain." The Journal

Floud, Humphries & Johnson, The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain

MacLeod, Christine, and Alessandro Nuvolari. Patents and industrialization: an historical overview of theBritish case, 1624-1907. No. 2010/04. LEM Working Paper Series, 2010.

Sullivan, Richard J. "The revolution of ideas: widespread patenting and invention during the English industrial revolution." Journal of Economic History (1990): 349-362.

J.R.R. Tolkien; Humphrey Carpenter, Christopher Tolkien (eds.), The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter 244, (undated, written circa 1963)

Nation-states are usually considered a modern phenomena, but considering Sauron’s big brother created Orcs in a pit and they are basically uniformly servants of Melkor/Sauron, I think the term is appropriate.

Banking as an emerging technology: Hoare’s Bank, 1702–1742

Quinn, Stephen. "The Glorious Revolution's effect on English private finance: a microhistory, 1680–1705."

Seghezza, Elena (2015). Fiscal capacity and the risk of sovereign debt after the Glorious Revolution: A reinterpretation of the North–Weingast hypothesis. European Journal of Political Economy, 38(), 71–81. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2014.12.002

North, Douglass, and Barry Weingast. “Constitutions and Commitment: The Evolution of Institutions Governing Public Choice in Seventeenth-Century England.” Journal of Economic History 49, no. 4(1989): 803-32.

Learning and the Creation of Stock-Market Institutions: Evidence from the Royal African and Hudson's Bay Companies, 1670-1700

Author(s): Ann M. Carlos, Jennifer Key and Jill L. Dupree

Temin, P., & Voth, H.-J. (2005). Credit rationing and crowding out during the industrial revolution: Evidence from Hoare’s Bank, 1702–1862. Explorations in Economic History, 42(3), 325–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2004.10.004

Neal, Larry. "How it all began: the monetary and financial architecture of Europe during the first global capital markets, 1648–1815." Financial history review 7.2 (2000): 117-140.

Rediscovering risk: Country banks as venture capital firms in the first industrial revolution

Perhaps this is an loan word from our English, but Tolkien is a linguistics guy and I doubt he would introduce words with implications he hadn’t considered.