The Bad Economics of Ghost Pirates

An entirely too thorough examination of Scooby-Doo: Pirates Ahoy! (2006)

Scooby Doo: Pirates Ahoy! is a bad movie. One reviewer describes the plot as “beyond moronic” and that “the writers and producers of this movie should feel bad about making it.”1 I agree.

This, however, does not seem to be a universal opinion:

Illustrious art connoisseur Only1Noble is incorrect. This movie is terrible.

For those who have not seen the movie, here is the plot:

A cruise ship hypnotist manipulates Biff Wellington, a knock off Richard Branson style billionaire, into thinking he is the reincarnation of Skunkbeard, a Caribbean pirate from 200 years ago. The hypnotized billionaire then funds a complicated criminal enterprise involving dressing up as the ghost of Skunkbeard (despite separately believing he actually is Skunkbeard) and attempting to kidnap an astrocartographer so that he can make him interpret a painting made by some unknown person that will lead to a magic meteor at the bottom of the Bermuda Triangle that he believes will allow him to travel back in time2.

In fact, the meteor can’t let you travel back in time (or maybe it can, it’s unclear), but it is made of solid gold, which is why the hypnotist wants it. This convoluted scheme is summarily thwarted by 4 meddling teens and their dog too3.

Like I said, this is not a good movie.

So why, dear reader, am I summarizing the plot and reviews of a terrible 2006 direct-to-DVD children’s movie to you? Because I believe in all of the national conversation, debate, and discussion surrounding this controversial film, a crucial element has been overlooked. A thesis so obvious that it shouldn’t even need to be elucidated has somehow eluded elaboration in the 16 years since this movie’s release.

Not only is this movie’s plot “beyond moronic” but the within the movie the villains’ plot is beyond moronic and they should feel bad about it.

While the “fake ghost pirate hypnotist” should be ashamed that I can call him a “fake ghost-pirate hypnotist”, in fact, the true villain of the piece is the billionaire who wanted to take the solid gold meteor back in time. Biff Wellington should be ashamed he even attempted, as if he had succeeded, he would have done permanent damage to the world economy. Moreover, I think a case can be made that the economic damage to the world would have been so bad as to make Wellington indirectly one of the greatest mass murderers of all time.

Undoubtedly, possessing a solid gold magic meteor would be personally valuable, and therefore Wellington may be optimizing for his own utility. However, I think you probably can argue that Biff would probably end up worse off without access to the markets for modern goods and giving up his Billionaire status. But, Biff Wellington doesn’t get utility from being a rich billionaire. No, Biff Wellington is trying to go back in time and (inadvertently) crash the world economy so he can do the one thing in the world that makes him happy, develop scurvy while trying to earn a meager living off of preying on merchants.

And that, dear reader, not his undead pirate persona, is what makes him a monster.

So, to be crystal clear, I am arguing that the introduction of this solid gold meteor via time travel to the world economy of 1806 (200 years before the movies came out in 2006) would have had disastrous knock-on effects leading to significant harm and suffering.

I propose the following plan of attack: First, we need to size and value the meteor. From there, we can move into evaluating exactly how disastrous the introduction of this much gold would have been for the world. My considered opinion is that there are three ways this meteor is going to cause problems when it pops up in 1806. First, it is going to inject an unfathomable level of wealth into the world economy which is going to absolutely, totally, and completely destroy British governance and manufacturing. Second, the large influx of gold will devastate the French Bimetallic currency regime, throwing world trade into chaos. Third, the mystic powers of the meteor will have adverse weather effects by unleashing the unceasing winds of the damned. After estimating these effects, I spitball some rough calculations to guess at what the total loss of life would be.

I. Scooby-Doo in Where’s My Meteor?

Before we get into evaluating what a massive increase in the supply of gold would have done to the historical economy, we need to figure out is exactly how much gold would have been injected into the economy.

Eyeballing this, I’m going to put the height of the meteor at about three and a half large pirates or 21ft, giving us a radius of 10.5ft.

We can then plug that in to the equation for volume of a sphere.

Volume = 4/3 x π x r^3

This gives us a volume of 4849 cubic feet.

Now that doesn’t necessarily seem like an insane amount of gold, but you need to know that gold is really dense. Like really, really dense.

Here’s a visualization of one ton of gold4.

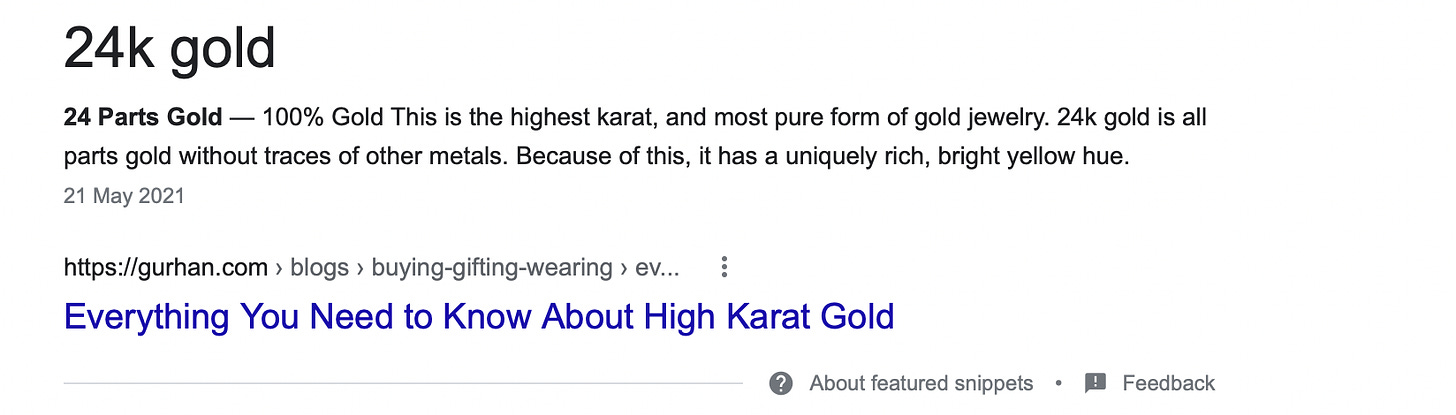

The meteorite is a lot bigger than that. To get specific numbers, we need to convert the volume into a weight. I’m going to assume the meteorite is pure 24k gold because A. They say in the movie that it is “pure gold” and B. The meteorite literally glows, which suggests a certain level of metallic purity and/or witchcraft (more on the latter, later).

24 karat gold has a density of approximately 1206 pounds per cubic foot5, giving us a total weight of gold of 5,847,894 pounds.

If we then convert this into metric tons we get 2652.560099 or ~2652 metric tons.

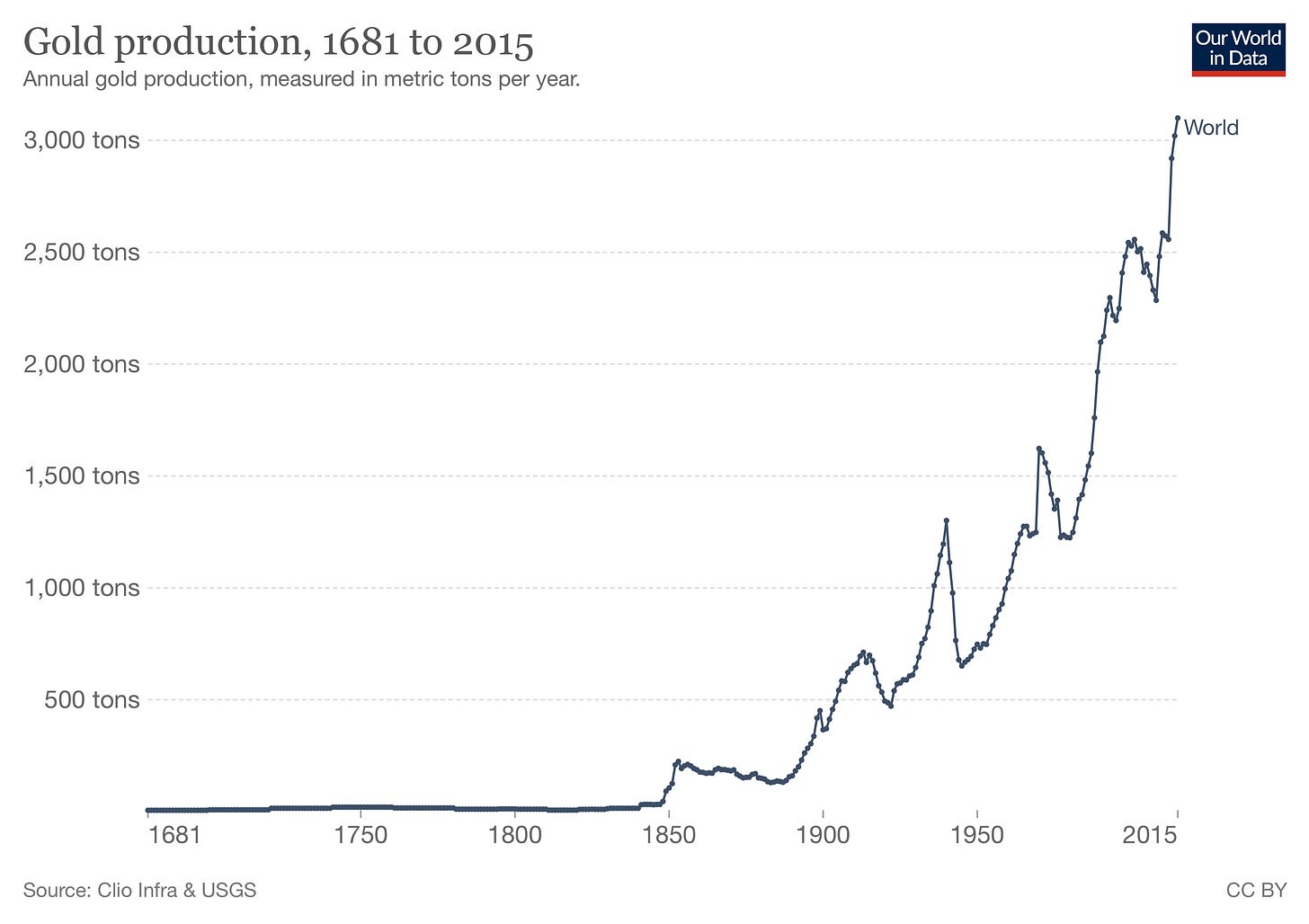

Okay, but how much gold is this relative to global production in 1806? Quite a lot, it turns out.

Our World in Data (god I love this website) has estimates of global gold production in 1806 at 11 metric tons.6

So, assuming my figures are even ballpark correct, this meteorite would have about 200xed the global supply of gold. For some (dubious) historical comparison, Mansu Musa allegedly wrecked havoc on Egypt’s gold valuations using just an extremely high-end ballpark of 10 tons of gold dust, 1/260th the weight of our meteor7.

So, having established that the meteorite’s mass. We can now think about what injecting that much gold into the economy is going to do.

II. Scooby-Doo: Curse of the Dutch Demon

The first place I think the meteor would have done serious damage is to the local economy of the pirates. This is a pretty counterintuitive claim! We would usually think that increasing the resources available to an economy would be beneficial to it. But, there’s actually some decent historic evidence that this isn’t the case. The general term for this phenomena is “Dutch Disease '' which is taken from the negative effects to Dutch levels of manufacturing following a sudden boom in natural gas prices. More generally, it refers to the pernicious economic effects of a resource windfall.

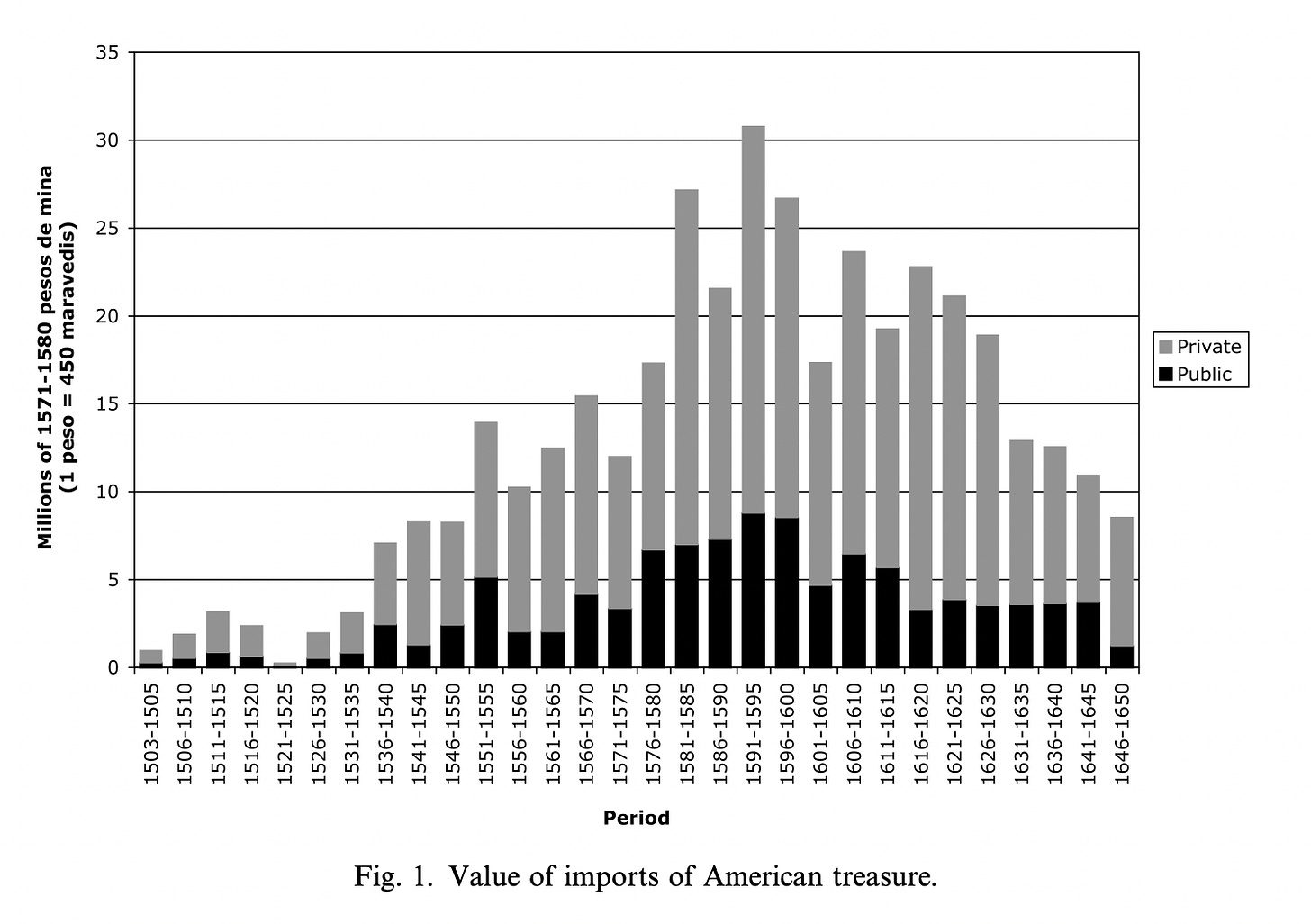

The clearest parallel to a hypothetical Golden Meteor injection is Spanish extraction of silver in the Americas. The 1500’s saw a significant increase in the flow of silver into Spain that approaches the magnitude of precious metal inflow that the meteor would cause.

Mauricio Drelichman has a great paper looking at the effect of this bullion increase on the Spanish economy.8 He argues that the sudden increase in wealth from the natural resource of silver caused a fundamental structural change in the Spanish economy.

The logic here is that a sudden increase in income raises the price of non-tradable goods relative to tradable ones. This is because (basically) as the incomes of consumers in the economy increase they will want to buy more stuff (demand for goods and services increases)9.

This higher demand for goods isn’t necessarily bad, however, the price of tradable goods is less elastic than the price for non tradable goods (as it is determined by global demand) inducing a relative rise in the price of non-tradable goods (there are also other mechanisms that can motivate this, see Edwards 1984)10 To put this in simpler terms, we should expect the price of goods and services that can’t be made by someone in a different country to increase faster, because there are fewer people who can do these jobs (think about the price of a haircut rising faster than the price of manufactured goods in the USA, its not because we’ve gotten worse at haircuts, its because we have to pay someone local to do it).

Drelichman finds empirical evidence of this in the case of Spanish Silver finding that:

“traded goods output could have been reduced by between 10 and 20% for a period of over 25 years; such a shift in production could hardly have been beneficial once the economy had to adjust to its post-boom reality.”

Okay, but why does this matter? All we’ve found evidence of is that types of goods produced in Spain changed, why does this sort of change have to be negative? There are a couple of reasons for this and I think it is worth separating them out and taking them piece by piece rather than mixing them together.

II.A Lower Human Capital

So the first problem is that non-tradable jobs tend to be less skilled and require less formal education. These are often service sector jobs (e.g. the haircut example above) where the reason it is non-tradable is the work is based primarily on physical presence. A version of this argument is made by Asea and Lahiri (2009)11 who do a bunch of math and some empirics to show that resource windfalls can lower a country’s human capital by reducing incentives to invest in skill formation.

This is obviously bad, we generally think education is important. But it is disastrously bad when we consider the very long run effects. Remember, Biff Wellington is planning to take this gold back in time to 1806. Shifting down the amount of education acquired historically has potentially exponentially devastating effects on the economy because the effects of human capital are persistant. Your historical levels of education have very long run effects on present economic growth. For the sake of time I won’t go too in depth on the evidence we have for this, but Hornung (2014)12 and Rocha, Ferraz and Soares (2017)13 are great papers that demonstrate this persistence by looking at exogenous shocks to human capital. The latter of those papers finds that an 8% higher literacy rate was associated with 15% higher income per capita 80 years later. So, declines to education are a big deal

II.B Institutional Degradation

So, all of this gold is going to make people less productive in the country it lands in. What is it going to do to the government? Well, nothing good. The basic problem is that when you suddenly create a large supply of valuable resources that don’t require incentivizing entrepreneurship/wealth-creating behavior you are going to provide a government with more opportunity to engage in poor fiscal behavior.14 In modern day this might look like excessive spending on infrastructure or other services, but in a historical economy it probably is more like that there is greater incentive for the monarch to expropriate and seize control of wealth rather than encourage investment by restraining themself. Once this shift towards bad governance occurs, we have some reason to think that it is going to stick around. A richer monarch is a monarch that is harder to dislodge or work around and they will have more resources to try to extract again in the future.15 So, there is probably some path-dependency in governance types.

II.C Manufacturing

Finally, increasing wealth and shifting the type of goods consumed is probably going to undermine manufacturing. This is a pretty straightforward conclusion from the shift towards non-tradable goods. Manufactured goods are almost by nature exportable and so the incentive to engage in them is lower. Additionally, this loss in manufacturing capabilities might have similar path dependent features to the government problem above. If we think industries learn and get more efficient over time, then we would expect at least a partial ‘lock-in’ effect whereby it becomes more and more costly to specialize back into manufacturing as time goes on.16

II.C Bringing it back to the meteor

So, there’s pretty good evidence that a sudden increase in the gold supply would harm the local economy of wherever the pirates are from. But there’s an additional question here: where are the pirates from? I don’t think there’s great evidence here. We know they roam the Bermuda Triangle but other than that we don’t have any evidence.

Or do we?

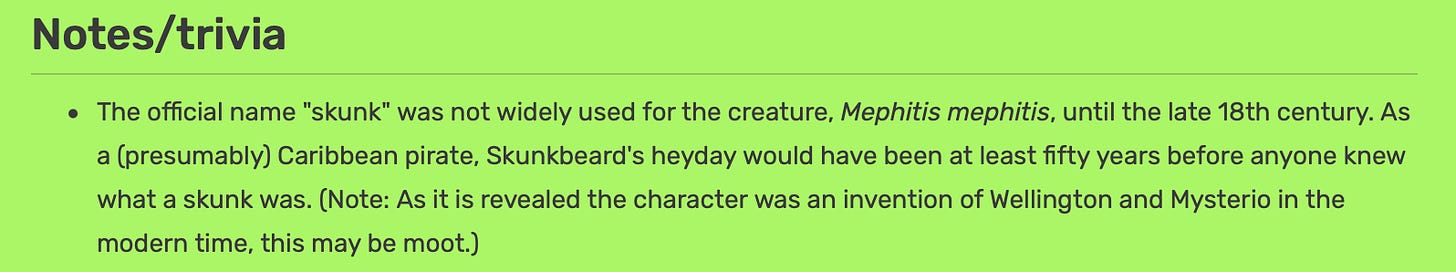

As I was contemplating this critical question I navigated to the Scoobypedia page for the leader of the pirates, the ghost of Captain Skunkbeard, and stumbled upon this bit of historical trivia17:

As far as I can tell (through a couple google searches), this fact is sort of true? At least as far as wide spread adoption of the name goes it was mostly post the time-period Skunkbeard was operating in.

This is important because the origins of the word Skunk are Algonquin, an indigenous language spoken by people who reside primarily in the northern United States and Canada18. So, for Skunkbeard to have been named Skunkbeard, he needed to have sustained interaction with native people in North America.

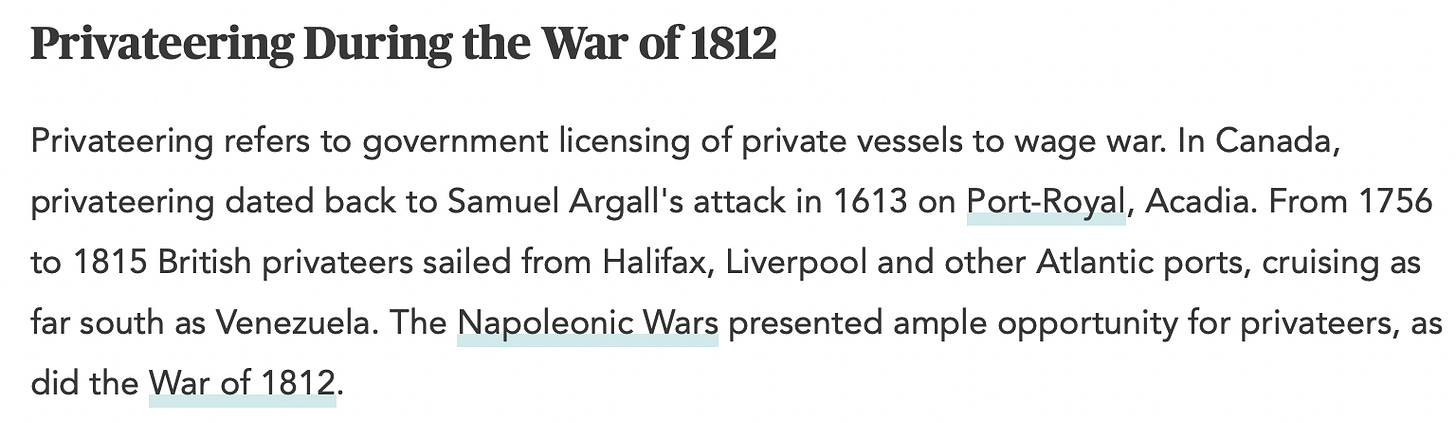

Now, why would a pirate circa 1806 have sustained interaction with northern indigenous groups to the point he adopts a term from their language as his nickname? My theory? Skunkbeard is a part of a long tradition of Canadian Privateers and was likely operating on behalf of the British crown during the Napoleonic Wars and the lead up to the War of 181219 Now, you don’t have to agree with my specific privateer theory to think it is likely that Skunkbeard is, at least in some way, connected to the economy of the British empire given his name.

So, if this lesser thesis holds, we would expect the blowback to be on the economic zone that was the British Empire. when Wellington attempts to take the role of Skunkbeard for himself. This is quite significant! Britain played a large role in the industrial revolution and anything that deterred that would have had significant knock-on effects on global economic growth.

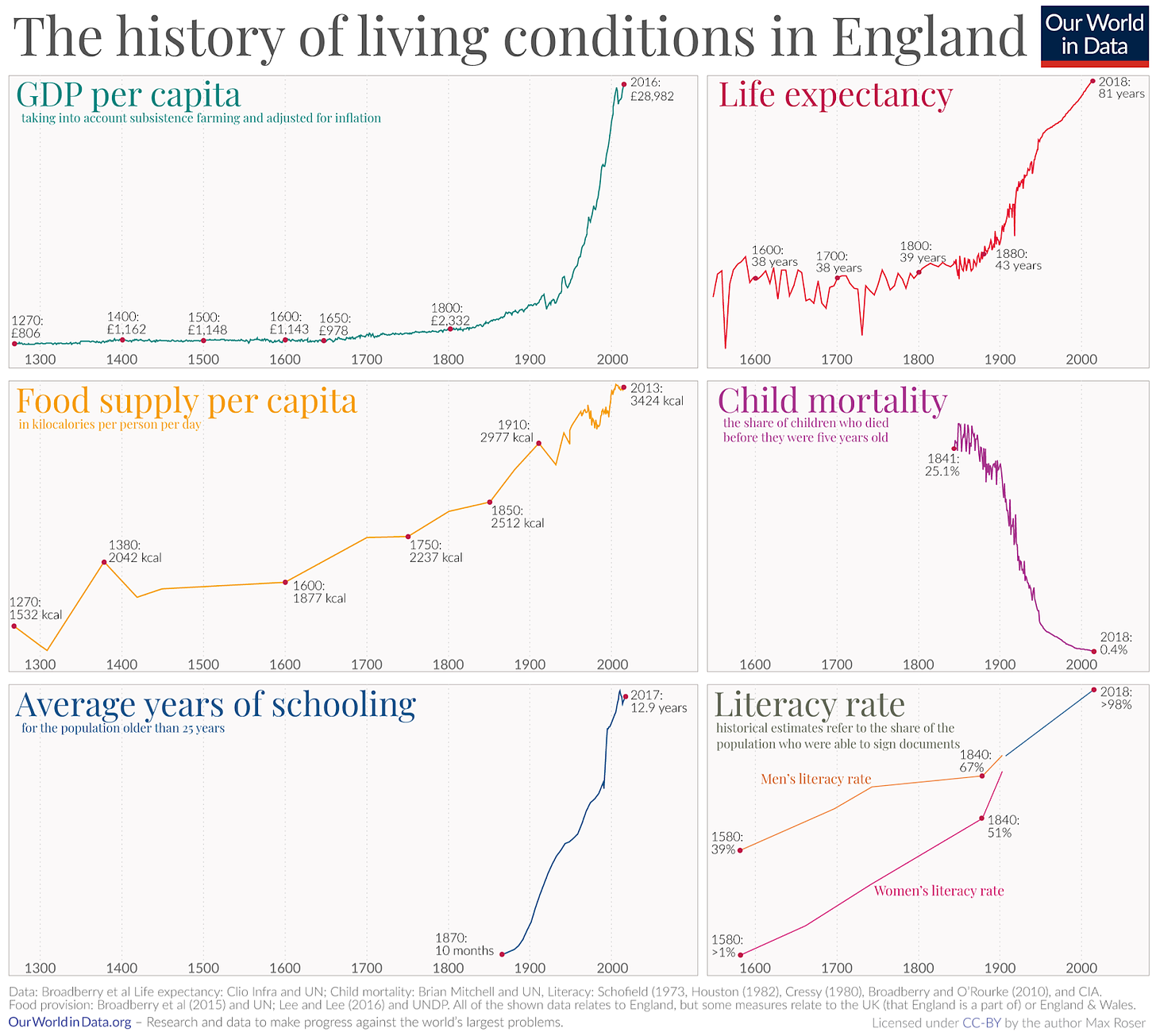

Specifically, Britain’s early industrialization (usually theorized to be caused by some combination of factor prices, wage rates, human capital, and governance)20 probably lowered the costs of additional countries adopting manufacturing technology. In our counterfactual, Britain has less education, lower incentives to invest in capital (because of an expropriative monarch), and will see lower relative returns from the manufacturing sector, all things that will delay or even stunt the industrial revolution, which, you know, was pretty good for human wellbeing.21

III. Scooby-Doo: Blowout Bimetallic Bash

The problem with the meteor gold shock is not just the injection of gold as a resource. It’s also an injection of gold as money. Almost all major economies in the 1800’s fixed their currency to some quantity of precious resources.22 That is, one unit of say a British Pound could be exchanged for some fixed quantity of gold. To simplify, if I dug up a pound worth of gold I could take it to the Bank of England and receive a pound coin.

Why would countries pin currencies to commodities? A bunch of reasons really. For one, iIt probably helped countries signal to lenders that they wouldn’t print money to devalue their debts or engage in general fiscal irresponsibility23. But for our purposes, the main effect of fixing your currency to a metal is that it significantly helps with international trade24.

Historical trade is risky and takes a long time to complete. Merchants trading between countries are worried that by the time they arrive at their destination either the price of goods or the price of the currency they are being paid in will have fluctuated reducing their profits or leaving them in the hole. Merchants could engage in some clever financial engineering to try and hedge risk, but this came at a cost of both expected profits and time. One way to alleviate some of this friction is to trade between countries that are pegged to the same commodity. This implies that the ratio between the currencies will remain fixed, alleviating any worries about showing up on the other side of the atlantic and realizing that the currency you just got paid in is now worth squat.

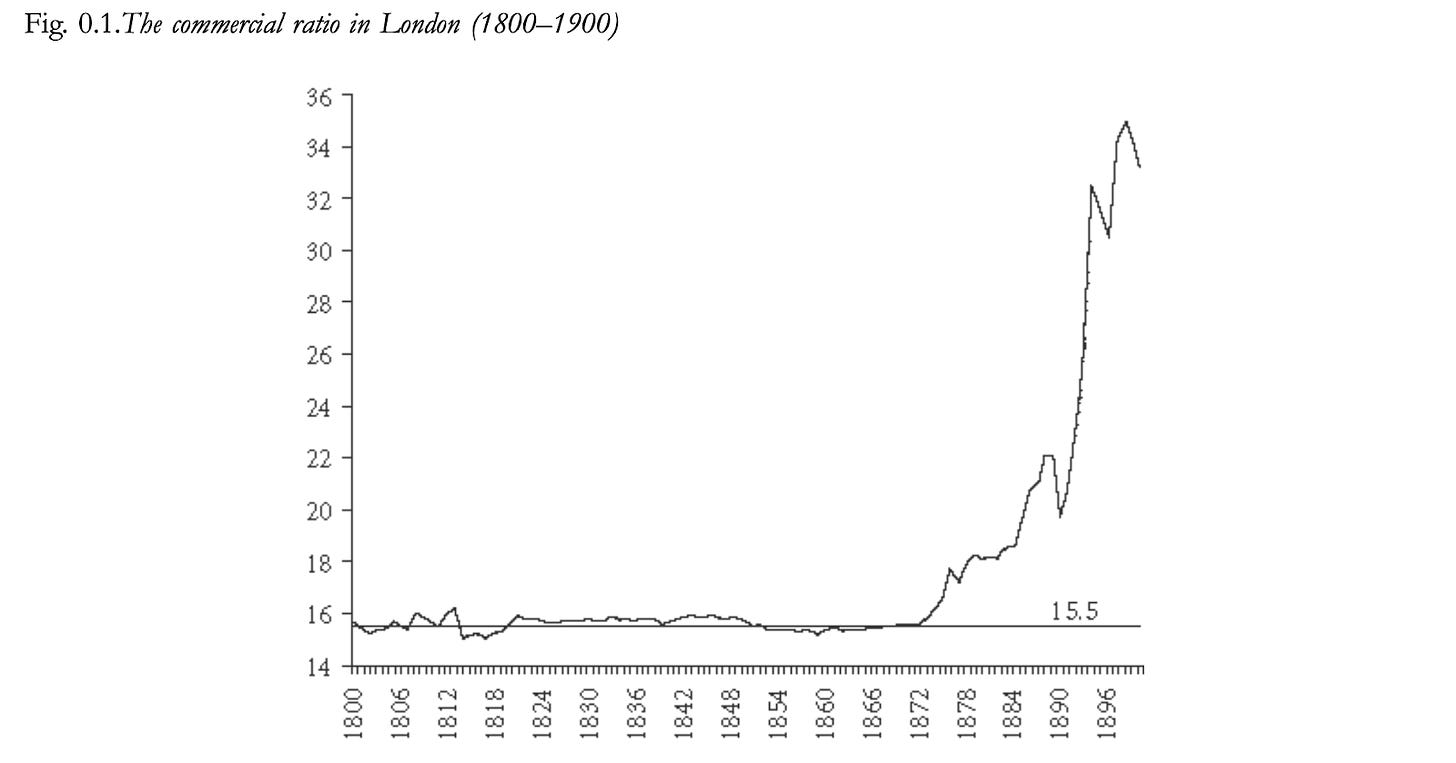

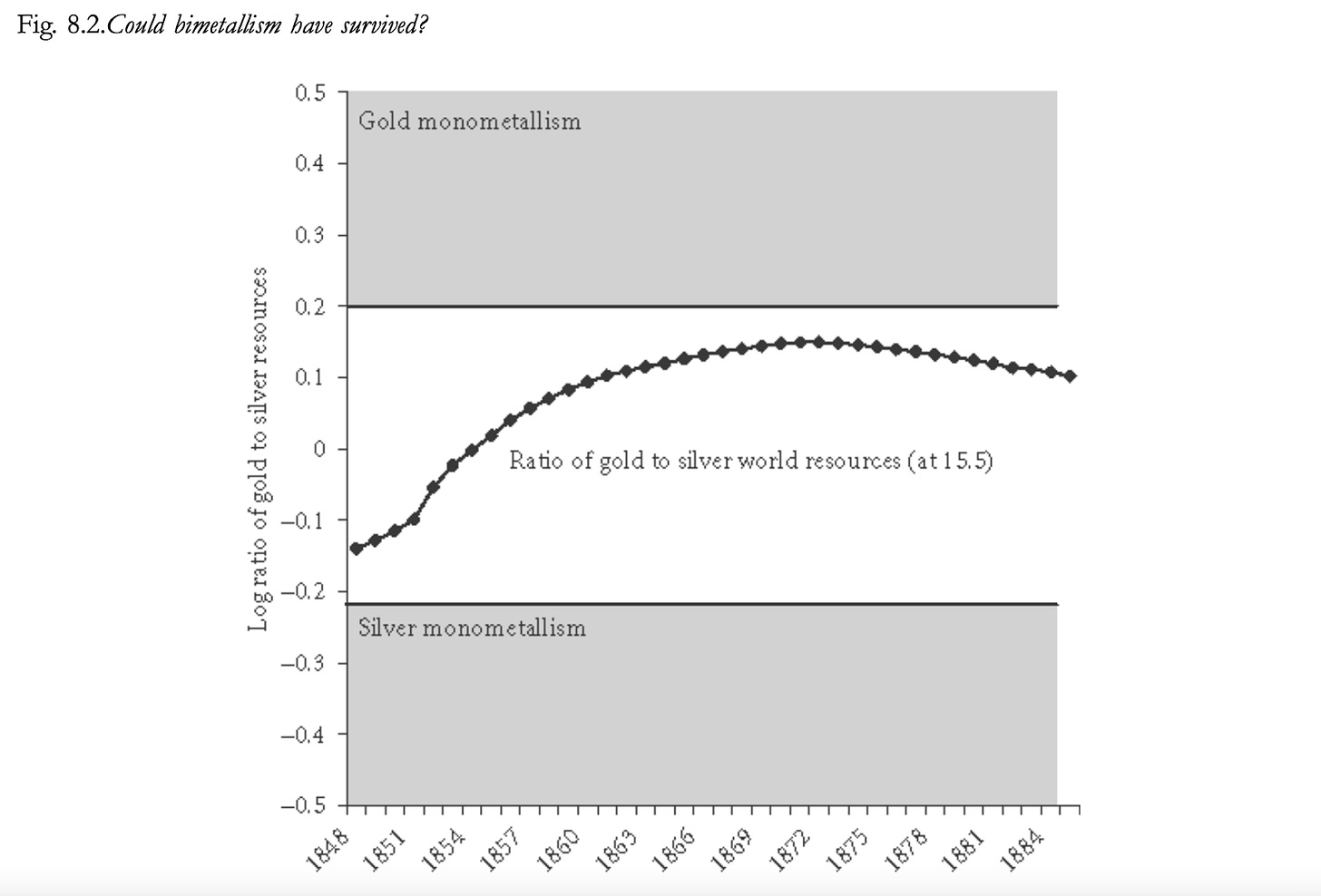

“Okay,” you say “That is a very interesting history of metal standards that you have abridged far beyond the point of usefulness, but what does this have to with my favorite childrens movie involving a talking dog?” Hold on, I promise I’m going somewhere with this. In the 1800’s you had basically three types of metal standards. You had your classic gold standards like Britain. You also had countries that instead pegged their currency to silver like most of east Europe and Asia. Now an important insight here is that the mechanism I described above to reduce trade costs only works within each of these systems. Theoretically, the price of silver and the price of gold can fluctuate relative to each other. So trading between a silver standard country and a gold standard country isn’t going to achieve the same level of stability as trading within gold or silver countries. At least, that would be true if it wasn’t for our third type of monetary regime which was bimetallism. These countries, mainly France if we’re being honest, fixed the price of their currency relative to both gold and silver. So you could exchange one Franc for either X amount of gold or Y amount of silver. In practice, this ratio was fixed at 15.5/1 Gold-to-Silver by France’s Germinal Act of 1803 (three years before the arrival of the meteor)25.

Bimetallic regimes functionally fixed the problem of gold and silver prices fluctuating against each other by becoming “arbitrageurs of last resort”. If the market ratio of gold and silver differed from 15.5, enterprising individuals could (roughly) exchange the lesser valued metal for the higher one at the Banque de France until prices were brought back in line with the required rate. This functionally kept gold and silver at a fixed exchange rate globally until France’s move away from bimetallism in the 1870’s.

So, if bimetallic regimes arbitrage away fluctuations in the gold-silver price ratio, why would we expect the injection of gold to do anything to currency? Well, arbitrage works until it doesn’t. Simplifying somewhat, to be able to exchange silver for gold the Banque de France needs to have sufficient reserves of specie on hand that they will be able to exchange one for the other. If the ratio of gold to silver deviates beyond an extreme point, the Banque de France wouldn’t be able to pull the exchange rate back into line, effectively destroying the fixed rate of exchange and allowing the ratio of gold to silver to fluctuate with the market.

Flandreau (2004) estimates the boundaries of sustainable market gold-silver ratios as follows (noting that these estimates are for a slightly later time period):

Our ~2000 ton meteor is going to bring the ratio way past these bounds. My napkin math suggests that (making an overly generous assumption of an average of 5 tons of gold extracted a year) the meteor is equivalent to the world production of gold from 1276-1806, more than enough to create the shock needed to destabilize France.

This destabilization is going to allow for fluctuation in gold prices, undermining international trade and slowing economic growth. Furthemore, this harm to trade isn’t even factoring into account the rise of an unfathomably wealthy pirate lord whose only apparent goal in life is to be the best pirate possible, which surely wouldn’t have any positive effects on trade.

IV. Happy Hurricane, Scooby-Doo!

Finally, we need to discuss the climate effects of the meteor. Up till now, I have discussed the gold-based economic effects of the meteor and ignored the economic effects of the vengeful spirits of those damned and drowned. Because, of course, the meteor is not just a gold meteor, it is a magic gold meteor. We have clear textual evidence that the removal of the meteor from its resting place at the bottom of the Bermuda triangle induces a ghost-powered approximation of a hurricane until it is returned to the deep26.

As, sadly, the economic literature on vengeful spirits is sorely lacking, I propose drawing on some literature of hurricanes generally. Hurricanes, as it turns out, are econometrically somewhat difficult to measure. Post-impact we see an influx of insurance payouts and aid packages that results in a broader distribution of the costs, so we can’t simply measure the economy of an area before and after a strike. Some estimates put the economic loss to a US county being hit by a hurricane at around a .8% decrease in growth initially before aid rushes in, but this still might not be appropriate27. The modern US has a much higher capital stock and more sophisticated infrastructure than historical economies and as such might be much more vulnerable to adverse weather effects. Fortunately for us, Mohan and Strobl (2012) provides an estimate of exactly what we are interested in, as they look at the effects of hurricanes on the economy of Caribbean countries from 1760-1900 and find that a hurricane hiting a country reduced sugar exports by ~33 million pounds in the next 2 years28.

How should we generalize this result to our meteor? I think conceptualizing our scenario as an essentially constant low-grade hurricane seems appropriate. I’m not sure we can get a precise number in terms of economic impact for that (because it doesn’t seem right to generalize the above finding to a constant, unending storm). But I would feel comfortable spitballing it somewhere between tremendously unfortunate and real real bad.

V. Scooby-Doo and Economic Growth’s Ghost

Okay, so we’ve got a bunch of random bad things that our genius billionaire pirate-weeb either doesn’t care about or hasn’t considered, what does this actually mean for the world economy overall? I’m not going to try to estimate a value for a couple reasons. First, because each estimate in the above sections is highly uncertain, so sticking them together is just going to generate a basically uselessly error-prone guess. Second, because it would be hard and take a long time and I’m lazy.

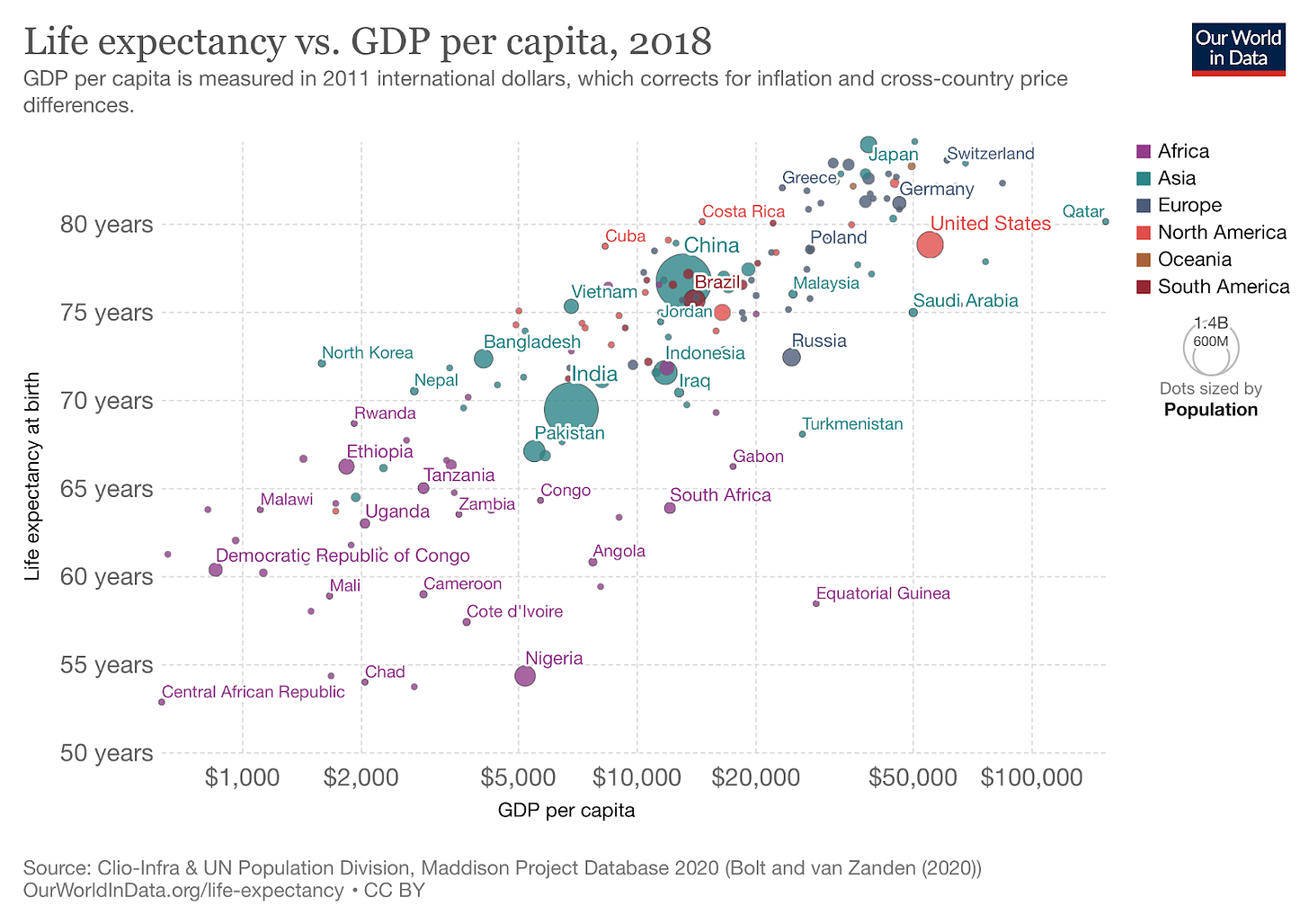

Fortunately, because we are dealing with such long time frames, I don’t think I need to. The change in US (just picking this as an example) GDP per capita is reasonably approximated as a 1.67% increase a year in the long run29. If we think that A. Crippling Britain’s industrial revolution B. Undermining international trade and C. Eternal storms of vengeance would knock down that growth rate by .25% (which seems very much like a lowball to me?) that would reduce modern day incomes by around $10,000 a person. If we conjoin this with assumptions that the positive relationship between GDP and life expectancy is even somewhat causal, then that's like a lot of people that our Blackbeard otaku has killed30. Even if you play around with the numbers and scale them down, you still end up with millions of lifetime equivalents being cost from a small downward shift in historical growth.

Assuming an average life decrease of 4 years and that only 1 billion people have lived since 1800 that gives us a total decrease in life-years of 4-billion. Converting this into 65 year lifespans that gives us a loss equivalent to ~65 million lifespans. Again, this may be perfectly rational from a utility maximizing perspective, but, for some reason, I doubt that someone who seems to have made his fortune in Jetpacks would be thrilled by the level of economic devastation that he will unleash.

So, what should you do with this knowledge that a Scooby-Doo villains plan was orders of magnitude more evil than you thought? Personally, I propose rioting in the streets. Barring that, perhaps a campaign to recut the movie to make Wellington’s plan less horrifying, something I’m sure the director would have preferred had he thought about it. That’s why I’m calling on every citizen of upright moral character to join me in asking Warner Brothers to #realeasetheSheetzcut and fix this egregious error.

Footnotes:

https://manapop.com/film/scooby-doo-pirates-ahoy-2006-review/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scooby-Doo!_Pirates_Ahoy!

Ibid.

https://demonocracy.info/infographics/world/gold/gold.html

https://chem.libretexts.org/Ancillary_Materials/Exemplars_and_Case_Studies/Exemplars/Everyday_Life/Conversion_Factors_and_Gold_Jewelry

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/gold-production

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mansa_Musa

Drelichman, Mauricio. “The Curse of Moctezuma: American Silver and the Dutch Disease.” Explorations in Economic History 42, no. 3 (July 2005): 349–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2004.10.005.

Ibid.

Edwards, S., 1984. Coffee, money and inflation in Colombia. World Development 12 (Nos. 11/12), 11071117.

Asea, P.K., Lahiri, A., 1999. The precious bane. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 23, 823849.

Hornung, Erik. "Immigration and the Diffusion of Technology: The Huguenot Diaspora in Prussia." The American Economic Review 104, no. 1 (2014): 84-122.

Rocha, Rudi, Claudio Ferraz, and Rodrigo R. Soares. “Human Capital Persistence and Development.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9, no. 4 (October 1, 2017): 105–36. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20150532.

Tornell, Aaron, and Philip R Lane. “The Voracity Effect.” American Economic Review 89, no. 1 (March 1, 1999): 22–46. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.1.22.

Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson Why Nations Fail : The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty. Ebook Central. London, 2012.

Krugman, P., 1987. The narrow moving band, the Dutch Disease and the competitive consequences of Mrs. Thatcher. Journal of Development Economics 27, 41–55.

https://scoobydoo.fandom.com/wiki/Captain_Skunkbeard

https://www.etymonline.com/word/skunk

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/privateering-during-the-war-of-1812

Allen, Robert C. The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective. New Approaches to Economic and Social History. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

And

Mokyr, Joel. The Gifts of Athena : Historical Origins of the Knowledge Economy. Course Book ed. Princeton, NJ, 2011.

https://ourworldindata.org/breaking-the-malthusian-trap

Flandreau, Marc. The Glitter of Gold : France, Bimetallism, and the Emergence of the International Gold Standard, 1848-1973. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Bordo and Rockoff (1996). “The Gold Standard as a “Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval”” The Journal of Economic History, 56 (2): 389-428.

Meissner (2005). “A new world order: explaining the international diffusion of the gold standard, 1870- 1913” Journal of International Economics, 66 (2): 385-406.

And

Lopez-Cordova and Meissner (2003). “Exchange-Rate Regimes and International Trade: Evidence from the Classical Gold Standard Era” American Economic Review, 93 (1): 344-353.

Flandreau, Marc. The Glitter of Gold : France, Bimetallism, and the Emergence of the International Gold Standard, 1848-1973. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

For some reason wikipedia says that it is a volcanic eruption instead of a storm. As far as I can tell that’s just not correct?

Strobl, Eric. “The Economic Growth Impact of Hurricanes: Evidence from US Coastal Counties,” n.d., 41.

Mohan, Preeya, and Eric Strobl. “The Economic Impact of Hurricanes in History: Evidence from Sugar Exports in the Caribbean from 1700 to 1960.” Weather, Climate, and Society 5, no. 1 (January 1, 2013): 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-12-00029.1.

https://ourworldindata.org/economic-growth

https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy